Genetic Mutations Linked To Higher Proportion Of ALS Cases Than Previously Believed

New research at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles indicates that genetic mutations may underlie more amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) than scientists had previously realized. The research results also revealed that the quantity of mutated genes influences at what age the fatal paralyzing disease symptoms will first manifest.

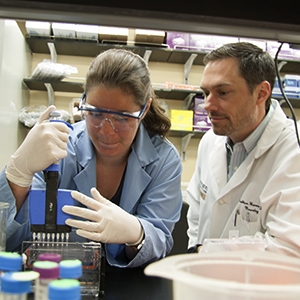

Washington University graduate student Janet Cady and assistant professor of neurology Matthew Harms, MD, found evidence that genetic mutations may contribute to more cases of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) than scientists had realized. The illness destroys nerve cells that control muscles, eventually leading to paralysis and death – Photo Credit: WUSTL

ALS, AKA Lou Gehrig’s disease, destroys nerve cells that control muscles. This damage leads to loss of mobility, impaired breathing and swallowing, and with increasing paralysis ultimately resulting in death. Understanding how genes contribute to ALS development is valuable to scientists in their quest for new treatments.

The WUSTL/Cedars-Sinai study, entitled: “Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis onset is influenced by the burden of rare variants in known amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genes” published online before print in the American Neurological Association journal Annals of Neurology, coauthored by Janet Cady BS, Taha Bali MD, Alan Pestronk MD, and Matthew B. Harms MD, of the Department of Neurology, Washington University, St, Louis, MO; Peggy Allred DPT and Robert H. Baloh MD, PhD of the Department of Neurology, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA; Alison Goate PhD of the Department of Psychiatry, Washington University, St Louis, MO; Timothy M. Miller MD, PhD of the Hope Center for Neurological Disorders, Washington University, St Louis, MO; Robi D. Mitra PhD of the Department of Genetics, Washington University, St Louis, MO; and John Ravits MD of the Department of Neurosciences, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA. Corresponding authors are Dr. Harms and Dr. Baloh.

The coauthors explain that in order to define the genetic landscape of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and to assess the contribution of possible oligogenic inheritance, their objective was to comprehensively sequence 17 known ALS genes in 391 ALS patients in the United States. They used targeted pooled-sample sequencing to identify variants in 17 ALS genes, with genotype-phenotype correlations made with individual variants and total burden of variants. Rare variant associations for risk of ALS were investigated at both the single variant and gene level.

They discovered that a total of 64.3 percent of familial and 27.8 percent of sporadic subjects carried potentially pathogenic novel or rare ALS gene coding variants, and these individuals experienced disease onset approximately 10 years earlier than subjects with variants in a single gene, although the number of potentially pathogenic coding variants did not influence disease duration or location of onset.

Mutations in any of the more than 30 genes scientists have linked to ALS, alone or in combination, can cause the disease in persons who inherit them, although the coauthors note that roughly 90 percent of patients with ALS have no family history of the disease, and their illness is categorized as sporadic ALS. Heretofore, scientists had thought gene mutation contributed to barely more than one in 10 sporadic ALS cases.

“To our surprise, we found that 26 percent of sporadic ALS patients had potential mutations in one of the known ALS genes we analyzed,” says co-senior author Matthew Harms, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Washington University. “This suggests that mutations may be contributing to significantly more ALS cases.”

“To our surprise, we found that 26 percent of sporadic ALS patients had potential mutations in one of the known ALS genes we analyzed,” says co-senior author Matthew Harms, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Washington University. “This suggests that mutations may be contributing to significantly more ALS cases.”

The research team used a Washington University devised sequencing technique at to examine 17 known ALS genes in the DNA of 391ALS patients. Reflective of the general ALS patient population, 90 percent of these subjects had no family history of ALS.

The scientists note that it’s yet unclear as to why some patients presenting with sporadic ALS carry genetic mutations linked to the disorder but have no family history of the disease. It remains as yet unknown as to whether these patients are first in their geneologic line to develop these particular mutations, or if the defective genes are present in other family members who for whatever reason don’t succumb to the disorder. Dr. Harms observes that some of the identified mutations might not contribute to ALS at all.

“It’s also possible that these mutations could be combining with environmental factors linked to ALS,” comments co-senior author and associate professor of neurology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Robert Baloh, MD, PhD,. “Those factors might coincide in an individual family member and cause disease, while other family members who have the mutation but not the environmental exposures remain unaffected.”

“It’s also possible that these mutations could be combining with environmental factors linked to ALS,” comments co-senior author and associate professor of neurology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Robert Baloh, MD, PhD,. “Those factors might coincide in an individual family member and cause disease, while other family members who have the mutation but not the environmental exposures remain unaffected.”

Dr. Baloh is Director of Neuromuscular Medicine in the Department of Neurology at Cedars-Sinai, and a member of the hospital’s Regenerative Medicine Institute Brain Program, as well as being director of the institution;a multidisciplinary ALS program and has authored or co-authored more than 40 articles on neurology and neuromuscular medicine.

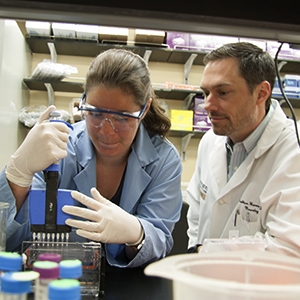

Led by Dr. Baloh, the Cedars-Sinai Neurodegenerative Diseases Laboratory’s objective is to better understand mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases including ALS and peripheral neuropathy, using human disease genes as their guides in aid of developing effective treatments for these neurological disorders. The Baloh Laboratory is affiliated with the Cedars-Sinai Regenerative Medicine Institute and the Neurology Department.

The WUSTL/Cedars-Sinai study also shows that carrying mutations in more than one ALS gene can accelerate symptoms onset which occurs at the median age of 61 for patients with only one gene mutation, but at just 51 in persons with more than one mutation.

The scientists will proceed with analyzing genetic data from additional ALS patients in order to confirm their results.

The ALS Association estimates that 30,000 Americans are suffering with ALS at any given time. Riluzole, the sole approved for treating the disease, is of only marginal benefit to patients.

This research project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers K08-NS075094 and R01-NS069669, and NIH Genetics Epidemiology Training Grant 5-T32-HL-83822-5.

Sources:

Washington University School of Medicine

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center

The ALS Association

Image Credits:

Washington University School of Medicine

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center