Protein Aggregates Seen to Rapidly Spread in Mice with Hereditary ALS Mutation

SOD1 protein aggregates can spread in a prion-like way, rapidly causing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) when injected into the spinal cord of mice carrying a human mutated SOD1 gene. The results, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, substantially advance insights into mechanisms in hereditary ALS, and may allow for the development of targeted treatments for SOD1-based disease.

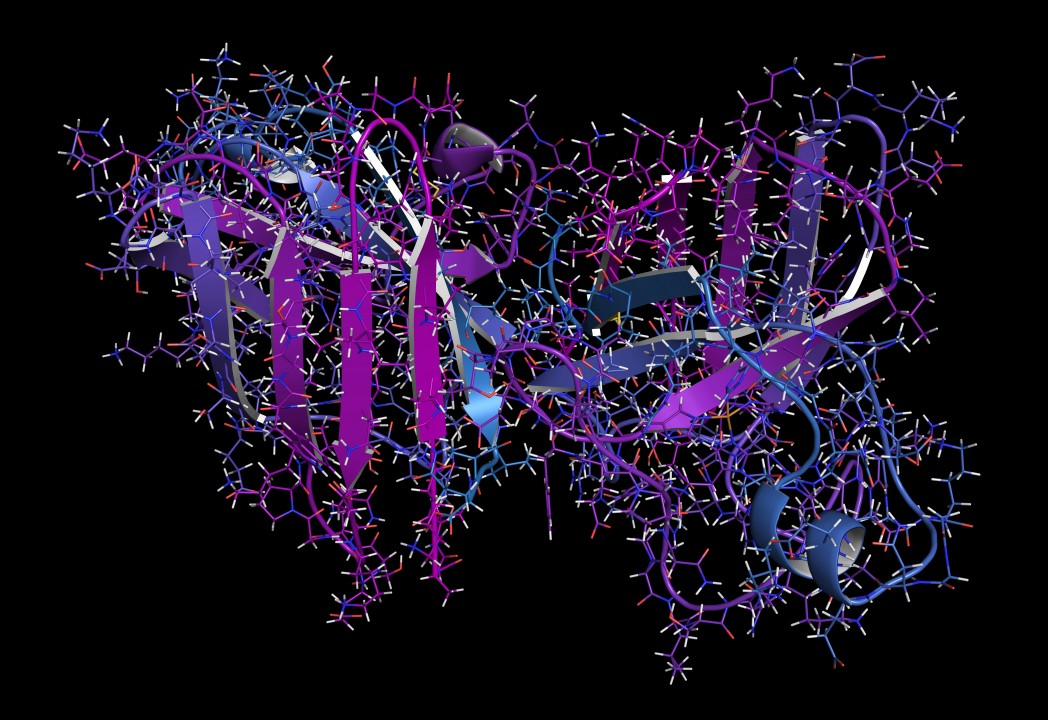

Mutations in the gene for SOD1, an enzyme protecting from the deleterious effects of reactive oxygen species, lead to an inherited form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Until now, researchers did not know if the SOD1 protein aggregates — observed in both patients and mouse models of the disease — actively contribute to the disease.

Recent studies have indicated that aggregates of SOD1 can spread between cells in culture, and that whole spinal cord extracts from paralyzed ALS mice hasten disease onset in newborn mice.

Researchers at Umeå University, Sweden, studied mice with a human mutant SOD1 gene, who start developing symptoms of ALS in their middle age and eventually die of the disease. In earlier publications, the research group has shown that such mice develop two kinds of SOD1 aggregates.

“The occurrence of SOD1 aggregates in nerve cells in ALS patients has been known for a while, but it has long been unclear what role the SOD1 aggregates play in the disease progression in humans carrying hereditary traits for ALS,” Thomas Brännström, a professor of Pathology at Umeå University said in a senior author, said in a press release.

Isolating both strains of protein aggregates and injecting small amounts back into the spinal cord of mice too young to display symptoms, the study, “Two superoxide dismutase prion strains transmit amyotrophic lateral sclerosis–like disease,” showed that the ‘seeds’ of aggregated SOD1 caused a spread of protein aggregation along the entire spinal cord of the mice, who also developed symptoms earlier than mice not receiving the seeds.

“We have now been able to show that the SOD1 aggregates start a domino effect that rapidly spreads the disease up through the spinal cord of mice. We suspect that this could be the case for humans as well,” said Dr. Brännström.

The disease also had a more aggressive course, with mice developing end-stage ALS after 100 days, about 200 days more rapidly than control mice. The two aggregate strains differed in several aspects, such as distribution in the spinal cord and progression.

“The results show that the aggregation of SOD1 plays a critical role in the disease progression — a research hypothesis that ALS researchers in Umeå long has based its work upon,” said Stefan Marklund, a study co-author and professor of Clinical Chemistry at Umeå. “More research is necessary, but our aim is to develop interventions that prevent or stop the fatal course of the disease in carriers of hereditary traits of ALS.”