#AAN2022 – How Environmental Exposure Affects ALS Risk Is Studied

Written by |

Researchers at the University of Michigan are focused on establishing cause and effect relationships between environmental and occupational exposures with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

They hope this information will shed light on the mechanisms behind the disease and identify modifiable risk factors, which may have implications in preventing ALS.

The team’s findings and goals were shared in an oral presentation by Eva Feldman, MD, PhD, the project’s leader, at the virtual 2022 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) Annual Meeting, April 24–26.

Feldman is the Russell N. DeJong professor of neurology and the director of the ALS Center of Excellence at the University of Michigan, and the presentation, part of a plenary session, was titled “Targeting the ALS Exposome for Disease Prevention.”

The frequency of ALS, which is caused by known genetic mutations in only about 15% of cases, is expected to increase in the U.S. by 70% by 2040. Feldman believes this is associated not only with an increasingly older population, but also with the ALS exposome.

The ALS exposome is defined as “the cumulative effect of environmental exposures and corresponding biological responses across the individual’s lifespan,” Feldman explained. These exposures can include pesticides, pollutants, air pollution, and occupations.

When combined with genetic alterations that make the individual more prone to develop ALS, the ALS exposome may trigger disease-associated neurodegeneration. This is called the gene-time-environment hypothesis.

Previous, unpublished research from Feldman’s team and collaborators identified 280 small genetic variants that together could predict the risk of ALS. These variants were used to develop a so-called polygenic risk score, which allowed researchers to distinguish ALS patients from non-affected people with a high degree of accuracy.

The researchers became particularly interested in ALS and the exposome because the disease’s frequency is highest in the Midwest (5.7 people per 100,000), which is both an industrial and agricultural region. In addition, clusters of sporadic ALS cases in the same neighborhood or households are common in Michigan, Feldman noted.

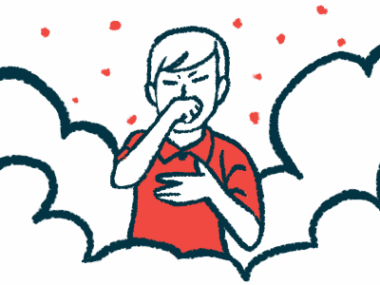

Feldman and her team previously found that exposure to multiple persistent organic pollutants (POPs), including organochlorine pesticides, brominated flame retardants, and polychlorinated biphenyls, increased ALS risk.

These pollutants, many of which were banned in the 1980s, are chemicals that remain in the environment “from years to decades to hundreds of years,” Feldman said, and “are all ingested by us and have very adverse nervous system effects.”

Feldman and her team also “quickly discovered that [a person is] not really subjected to just one pollutant, but … to multiple pollutants” over his lifetime. They developed an environmental risk score taking into account several existing pollutants, and found that, together, these compounds increased the risk of ALS by about sevenfold.

Higher exposures, as assessed by higher environmental risk scores, were also associated with shorter survival in ALS patients.

Additional, unpublished data also showed significant differences in metabolites, that is, intermediate or end products of cellular processes, between ALS patients and healthy controls based on the levels of a particular POP.

This suggests that “how we [process] these [pollutants] clearly affects the metabolites in our bodies,” Feldman said.

The neurology professor noted that increasing evidence points to the role of air pollution in developing ALS. The levels of the most commonly studied air pollutant, particulate matter PM2.5, are highest in the Midwest and most of the ALS cases in Michigan are located in areas with greater air pollution.

It’s believed that air pollution may interact with the immune system and trigger neuroinflammation, and the team found that ALS patients living in areas with the highest PM2.5 levels had the strongest inflammatory profile. These early data have not yet been published and further studies are needed to better understand these findings, Feldman noted.

The researchers have also looked at potential links between job exposures and ALS by surveying 378 ALS cases. They found that building, grounds cleaning and maintenance, construction and extraction, and production occupations were significantly associated with an increased ALS risk.

In the U.S., the rates of production occupations “are highest in the Midwest, where the highest prevalence of ALS exists,” Feldman said.

Based on these findings, “we advocate that there should be registries that facilitate correlating these measures of the ALS exposome to documented ALS cases and linking this to banked [biological samples],” Feldman added.

Also, to prove a cause and effect relationship between environmental risks and ALS, the team wants to establish registries to follow and collect samples from people who are more at risk, such as production or construction workers, for decades.

Moreover, the team has received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke “to take this combination of exposome measures that we have completed … [and] our polygenic risk score, and then look and integrate it with [molecular and metabolic data] from our patients,” Feldman said.

The idea is to develop “targeted mechanism-based interventions that focus on prevention.”

Several of Feldman’s team research has also been funded by Target ALS and the ALS Association.

Note: The ALS News Today team is providing coverage of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) 2022 Annual Meeting. Go here to read the latest stories from the conference.