Inflammatory bacterial sugar in gut may drive ALS risk: Study

Treatment to degrade glycogen could cut inflammation

Written by |

- Inflammatory bacterial sugar (glycogen) in the gut may drive ALS risk.

- This abnormal glycogen triggers inflammation, especially in C9ORF72-deficient cells.

- Degrading bacterial glycogen reduced inflammation and extended survival in mice.

Glycogen, an inflammatory sugar molecule produced by certain gut bacteria, may play a key role in driving amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a study found.

Treatments to degrade glycogen reduced inflammation and extended survival in an animal model of the disease, and clinical trials to test this approach in people with ALS could begin in the near future, the researchers said.

“We found that harmful gut bacteria produce inflammatory forms of glycogen (a type of sugar), and that these bacterial sugars trigger immune responses that damage the brain,” Aaron Burberry, PhD, a professor at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and a study co-author, said in a university news story.

The study, “C9orf72 in myeloid cells prevents an inflammatory response to microbial glycogen,” was published in Cell Reports.

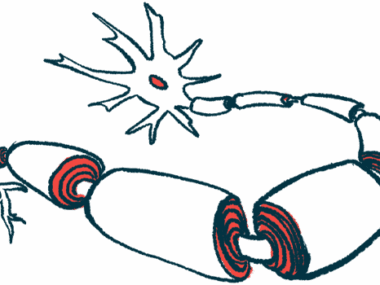

ALS is a neurological disorder marked by the degeneration and death of motor neurons, the nerve cells that control movement. The causes of ALS are unclear in most cases, but mutations in the C9ORF72 gene cause some forms of the disease.

Bacterial differences may explain why mice at some facilities live longer

To study ALS associated with C9ORF72 mutations, scientists have developed mice that lack this gene. Researchers in previous studies have observed that the survival of these mice depends on where they are housed. For example, mice with these mutations housed in a facility at Harvard have significantly shorter lifespans than those housed at the Broad Institute.

Scientists have linked these differences in survival to differences in the bacteria colonizing the intestinal tracts of mice across facilities. Data suggest that some gut bacteria can trigger an inflammatory response that worsens damage to the nervous system, though the mechanisms of how gut bacteria drive inflammation in these models aren’t fully understood.

Case Western scientists were working with C9ORF72-deficient mice and observed that the mice in their facility had significantly shortened lifespans, similar to what had previously been reported for mice at Harvard. This observation led the scientists to suspect that their mice might harbor pro-inflammatory gut bacteria similar to what had been observed at other facilities.

Sure enough, through a detailed battery of experiments, the researchers identified specific gut bacteria that triggered an inflammatory response in C9ORF72-deficient mice but not in mice with functional copies of the C9ORF72 gene.

The researchers conducted further analyses to determine exactly how these bacteria triggered inflammation and zeroed in on glycogen. This sugar molecule is naturally found in cells throughout the body, but the researchers found that pro-inflammatory gut bacteria make an unusually structured version of glycogen not typically found in human cells.

In mice lacking C9ORF72, this abnormal glycogen accumulates in myeloid cells, triggering an inflammatory response. This response was not observed in mice with healthy versions of the C9ORF72 gene.

The scientists found that treating C9ORF72-deficient mice at their facility with an enzyme that degrades gut glycogen significantly prolonged lifespan, supporting the idea that this bacterial glycogen might be a target for treating the disease.

“We … identify microbial glycogen as a therapeutic target to potentially mitigate risk of systemic [body-wide] and neural inflammation,” the scientists wrote.

While most of their experiments focused on mouse models, the researchers validated their findings using fecal samples from 35 people, patients and healthy controls. They found that inflammatory bacterial glycogen was detectable in fecal samples from 15 of 22 people with ALS, compared with four of 12 people without neurological disease.

The inflammatory glycogen was also detected in stool from one person with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), a disease that often co-occurs with ALS.

“Our demonstration that microbes that accumulate inflammatory forms of glycogen are enriched in the gut of ALS patients suggests that microbial glycogen may be an important example among many environmental and lifestyle factors that interact with predisposing [mutations] to contribute [to the] risk of ALS onset and progression,” the scientists concluded.

The researchers plan further studies to better understand why certain gut bacteria produce this inflammatory form of glycogen. They also hope to conduct clinical trials to test treatments aimed at degrading glycogen in people with ALS and/or FTD.

“To understand when and why harmful microbial glycogen is produced, the team will next conduct larger studies surveying gut microbiome communities in ALS/FTD patients before and after disease onset,” Burberry said. “Clinical trials to determine whether glycogen degradation in ALS/FTD patients could slow disease progression are also supported by our findings and could begin in a year.”