Electrodes Technique May Slow ALS Progression, Case Study Suggests

Written by |

A single-case study of a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) suggests that long-term invasive motor cortex stimulation via implants of electrodes may slow progression of the disease.

The study, “Reduction of disease progression in a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis after several years of epidural motor cortex stimulation” was published in the journal Brain Stimulation.

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a rapidly progressive, fatal neurodegenerative disease with no cure. The disease affects motor neurons (nerve cells) of the brain and spinal cord, i.e., those nerve cells controlling voluntary muscles.

Previous studies have shown that cortical hyper-excitability, meaning the part of the brain termed cortex is hyper excited (hyperactive), is an early characteristic of ALS. Most importantly, researchers hypothesize that it might trigger motor neuron degeneration in this disease.

Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques may modulate motor cortex excitability. In fact, several small studies have tested the potential of NIBS in ALS as a non-pharmacological therapeutic approach. The objective is to reduce excitoxicity (i.e., death of neurons due to excessive stimulation) in the brain of ALS patients. However, the results obtained in these small studies were contradictory. Moreover, NIBS has a major limitation because its effects are short-lived.

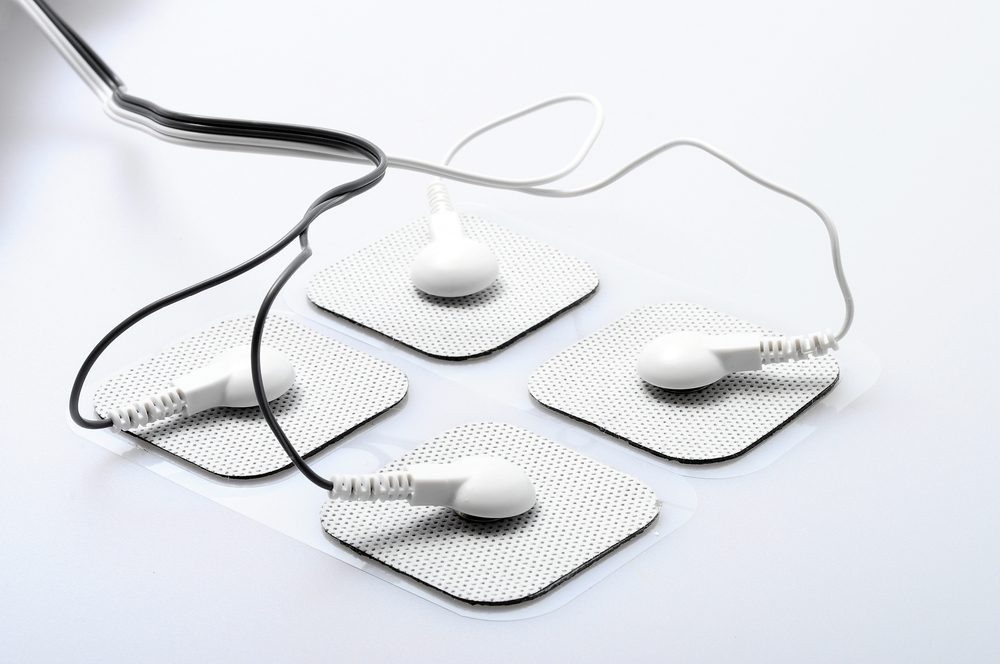

In this case, the authors evaluated the potential for a different technique, the invasive motor cortex stimulation. Implanted electrodes produce the same effects as NIBS. The difference, however, is that unlike NIBS, this technique can induce long-term effects.

They studied the effect of invasive motor cortex stimulation in a single patient, using epidural electrodes (electrodes placed in the spine, specifically in the epidural space). The patient was a 56-year-old male surgeon whose first symptoms began in 2004. The electrodes were implanted into his spine in 2006.

Electrode stimulation was performed for two months, 24 hours each day. Before the surgery, the patient exhibited rapid, progressive disease (progression was evaluated with the revised ALS functional rating scale, ALSFRS-R), in agreement with an aggressive form of ALS.

Even after authors tested several protocols for electrode stimulation, the rate of disease progression continued the following months.

Twenty-two months after electrode implants, and observing no improvements in disease progression, authors concluded that stimulation had no effect and stopped it.

Without doctors realizing it, however, the discharged patient continued the stimulation at home. He used the same frequency (3 Hz) authors tried in the past 10 months, but now for only 12 hours a day.

Stimulation was maintained for a year-and-a-half, until December 2009. At this point, the patient stopped feeling any benefit. Once doctors measured the rate of progression again, they noticed it was now at a mean of 0.1 points/month. During the stimulation in the hospital, the score was maintained at 1 point/month, which suggested a rapidly progressive and aggressive form of ALS. The patient reported no signs of depression or cognitive impairment.

Authors emphasized that this was a single case study, so no definite conclusions can be drawn. However, “these observations might motivate possible future exploratory studies evaluating the effects of invasive motor cortex stimulation in ALS patients,” they wrote.