Antibodies Preserve Nerve-Muscle Connections in Mouse Model of ALS, New Study Shows

Researchers at the NYU School of Medicine described a new strategy to preserve muscle function in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The finding could have implications for the treatment of alterations that occur in the early phases of ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

The study titled “Preserving neuromuscular synapses in ALS by stimulating MuSK with a therapeutic agonist antibody,” appeared in the journal eLife.

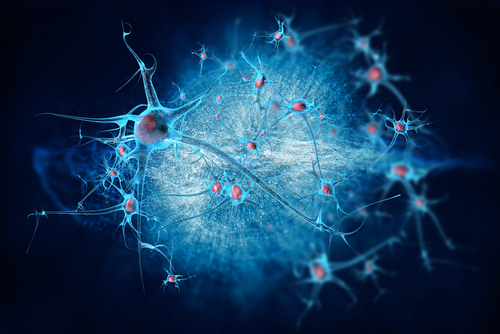

In patients with familial or sporadic forms of ALS, as well as in mouse models of the disease, the loss of motor neurons — which transmit signals to skeletal muscle cells, causing muscles to contract or relax — is preceded by damaged nerve-muscle connections (the neuromuscular junctions, or synapses). These alterations lead to a decline in motor function and, ultimately, lethal respiratory paralysis.

The research team used a mouse model of aggressive ALS (SOD1-G93A) to assess whether injecting mice with a muscle-specific agonist antibody to MuSK — a receptor essential for the formation and maintenance of neuromuscular junctions — would slow the detachment of nerve terminals from the muscle. The agonist antibody stimulates MuSK to increase signaling from muscle to nerve.

Results showed that injecting the antibody after disease onset (the first signs or symptoms of the disease) slowed the loss of neuromuscular synapses. A single dose of MuSK antibody increased the number of fully innervated neuromuscular synapses by 2.6-fold. In addition, chronic dosing induced a sustained increase in neuromuscular synapses for two months, and improved the function of the diaphragm muscle, which is key for breathing.

Moreover, the antibody improved motor neuron survival and extended the lifespan of ALS mice for about one week. This limited improvement in lifespan is due to the MuSK antibody strategy not targeting the underlying cause of the disease, the investigators observed.

“Our findings reveal a new therapeutic strategy for ALS that protects a pathway essential for keeping nerves and muscles connected,” Steven J Burden, PhD, the study’s senior author and a professor at NYU School of Medicine, said in a press release.

“There are few treatments for ALS, and the two FDA-approved drugs extend survival for only a few months in a subset of patients,” Burden added. Most experimental approaches have focused on stopping the death of motor neurons, which occurs in the later stages of the disease, the researchers observed.

“We believe that our approach, mostly likely in combination with other drugs, may extend quality of life during the early phases of this disease,” Burden said.