Device to Study Neurons and Muscle May Speed ALS Drug Discoveries

Engineers at MIT have developed a device that replicates the neuromuscular junction — the connection between motor neurons (the type of neurons that communicate and stimulate muscles, coming from the spinal cord) and muscle cells. The tool, which gives researchers access to technology in the lab that recreates how neurons stimulate muscles, could prove useful in the ongoing study of neuromuscular diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

“The neuromuscular junction is involved in a lot of very incapacitating, sometimes brutal and fatal disorders, for which a lot has yet to be discovered,” said Sebastien Uzel, from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at MIT, in a news release. “The hope is, being able to form neuromuscular junctions in vitro will help us understand how certain diseases function”.

Over the years, researchers have tried to study the connection between motor neurons and muscle cells using cultures of these two cell types in the laboratory. However, cell cultures are not able to maintain the three-dimensional environment of the body, which limits the study of this interaction to artificial conditions.

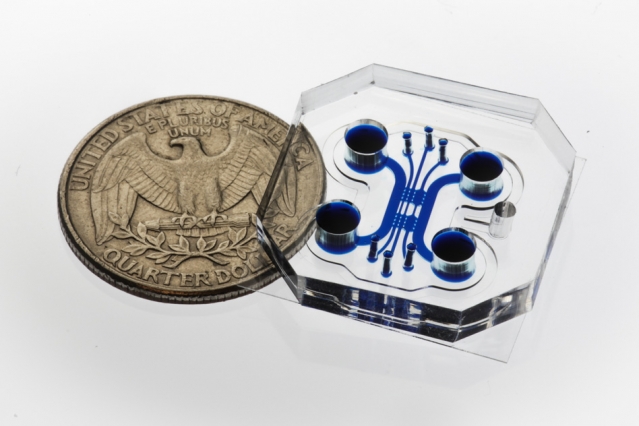

With this device, however, the researchers were able to create a more realistic neuromuscular junction in the lab. The device consists of a very small chamber (the size of a quarter) filled with a gel that creates a three-dimensional matrix in which neurons and muscle will grow separately in different compartments, similar to what happens in the body.

Researchers injected mice muscle cells in one of the compartments of the device, where the cells could grow and form a muscle strip. In the other compartment, they placed motor neurons that had been previously genetically modified to be sensitive to and activated by light, a technique called optogenetics. When researchers flashed blue light directly on these neurons they were stimulated, sending signals to the muscle cells, which in turn contracted or twitched.

“You flash a light, you get a twitch,” said Roger Kamm, PhD, Professor of Mechanical and Biological Engineering at MIT, and one of the authors of this study, in the news release.

The force of the contraction induced in the muscle cells also can be measured, as the device contains two small flexible pillars in the compartment where muscle cells are placed, around which the developing muscle fiber can wrap. Therefore, when neurons are stimulated, the pillars are squeezed together by the contraction of the muscle cells, causing a movement that can be measured and converted to mechanical force.

The team is confident this device can become very useful for future studies on muscular performance, or to test potential drugs for neuromuscular diseases in personalized therapies.

“You could potentially take pluripotent cells [immature cells that can become other cell types] from an ALS patient, differentiate them into muscle and nerve cells, and make the whole system for that particular patient,” Kamm said in the news release. “Then you could replicate it as many times as you want, and try different drugs or combinations of therapies to see which is most effective in improving the connection between nerves and muscles.”