Researchers Unravel Immune Mechanism Associated with ALS Progression

Researchers have discovered that mast cells and neutrophils — two types of immune cells — are involved in the degeneration of peripheral motor nerve cells and progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

These findings also clarify why masitinib — an investigational therapy for ALS that targets mast cells — might be an effective treatment for this severe disease.

The study, “Mast cells and neutrophils mediate peripheral motor pathway degeneration in ALS,” was published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation Insight.

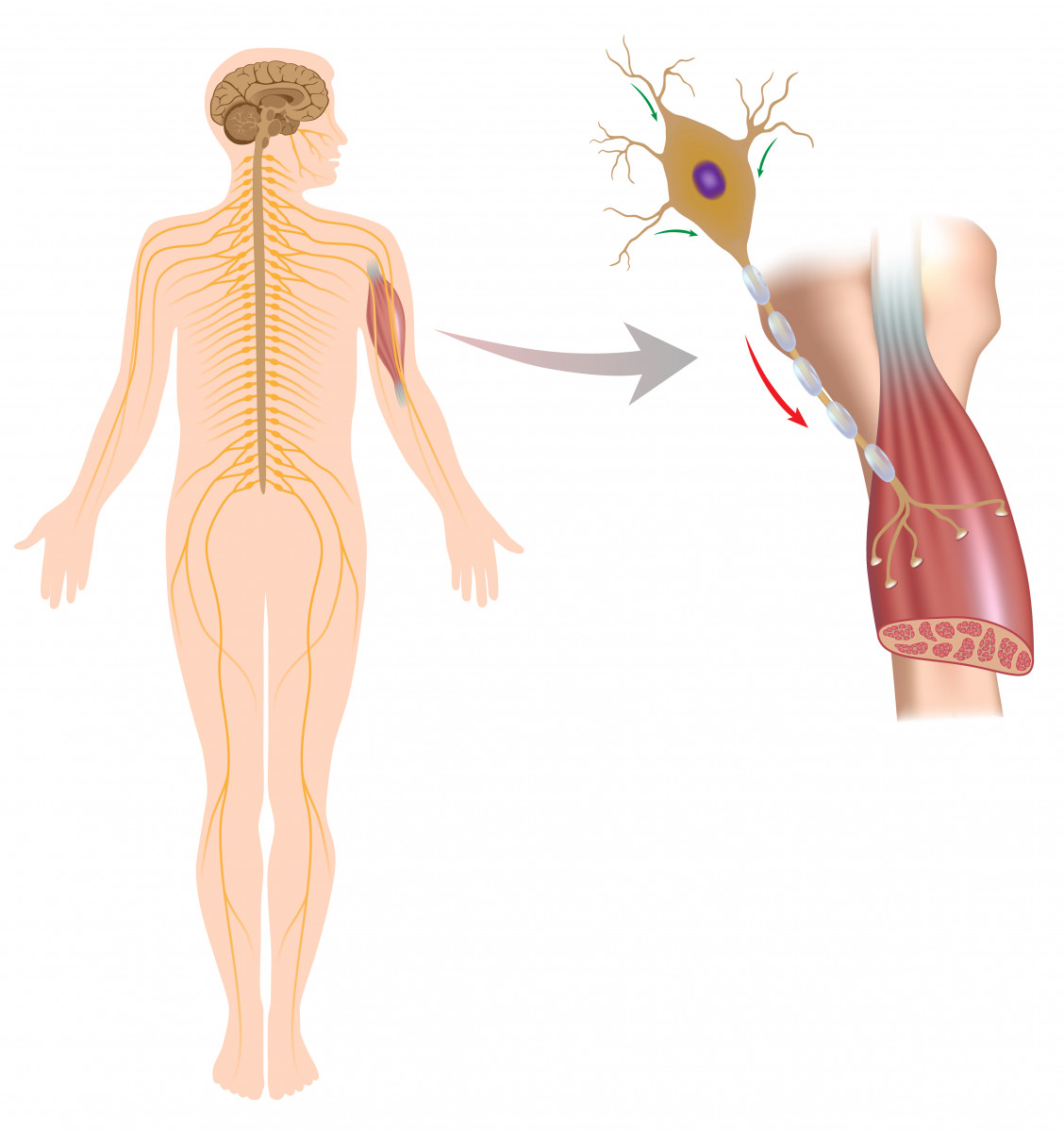

ALS is characterized by progressive weakness and paralysis caused by the degeneration of motor neurons. While inflammation — associated with reactive immune cells — is a known underlying mechanism of ALS in the central nervous system (spinal cord and brain), it’s still unclear how inflammation affects the peripheral motor nerve cells.

Motor nerve cells have their cell body in the brain or spinal cord and project their axon (fiber) to the spinal cord or directly to the muscle fibers.

Recently, mast cells — a type of immune cell involved in inflammatory responses — have been found to accumulate and be highly activated around degenerating peripheral motor nerve terminals and at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) after the onset of paralysis in a rat model of ALS. This suggested that mast cell infiltration and activation are associated with ALS progression.

The NMJ is the space between motor nerve cells and muscle cells where the nerve cell terminal induces a signal to the muscle cell to control its activation (muscle movement).

Mast cells can recruit and activate neutrophils, another immune cell involved in inflammatory responses and recently associated with neurodegenerative diseases. However, their potential association with ALS neurodegeneration has not been explored.

Researchers at the Institut Pasteur de Montevideo, the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Oregon State University, and IMAGINE Institute of Paris evaluated whether mast cell accumulation also occurred in skeletal muscles of ALS patients, and whether mast cells worked with neutrophils to cause further degeneration of peripheral nerves.

The team analyzed autopsied muscles from five ALS patients and five healthy individuals. They found that the numbers and activation level of both mast cells and neutrophils were significantly increased in skeletal muscles of ALS patients, compared with those found in skeletal muscles of healthy people.

These cells were also frequently found near the NMJ, suggesting that mast cells may be recruiting neutrophils and that they are working together in the degeneration of the NMJ, which affects the signaling between nerves and muscles.

Similar findings were observed in the muscles and sciatic nerves of a rat model of ALS, 15 days after the onset of paralysis. Researchers also found that activated mast cells and neutrophils were often found not only near the NMJ, but also around degenerated motor nerve axons in these rats.

These results show that these cells do accumulate throughout peripheral motor nerves and further support their association with neurodegeneration and ALS progression.

“We believe that immune cell attack is driving paralysis progression of ALS; neutrophils seem to be noxious effectors because they destroy and engulf axons and myelin [the protective sheath of nerve axons],” Emiliano Trias, PhD, the study’s first author and a postdoctoral researcher at Institut Pasteur, said in a press release.

Additionally, the administration of masitinib — known to block mast cell migration and activation — to ALS rats significantly reduced mast cell and neutrophil accumulation in muscle and nerve cells, preventing further motor nerve degeneration and disease progression.

This study reveals a link between what happens in this rat model of ALS and the underlying mechanisms of ALS in humans.

Additionally, considering that previous clinical evidence showed that masitinib – in combination with Rilutek (riluzole) – improved the functioning, survival, and quality of life of ALS patients, these data clarify its mode of action and provide “a stronger rationale for why Masitinib … might be protective in ALS,” said Joseph Beckman, PhD, one of the study’s authors and an ALS researcher at Oregon State.

“The present findings provide insight into immunopathogenic [immune system disease] mechanisms mediating peripheral motor pathway degeneration in ALS and underscores potential therapeutic approaches to delay disease progression,” the researchers wrote in the study.