Link Found Between Long-term Memory and ALS Neurodegeneration

Written by |

Researchers discovered that a small region of ataxin-2 — a protein known to be involved in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) — is crucial for both long-term memory and the formation of toxic aggregates that lead to neurodegeneration.

The study with that finding, “RNP-Granule Assembly via Ataxin-2 Disordered Domains Is Required for Long-Term Memory and Neurodegeneration,” was published in the journal Neuron.

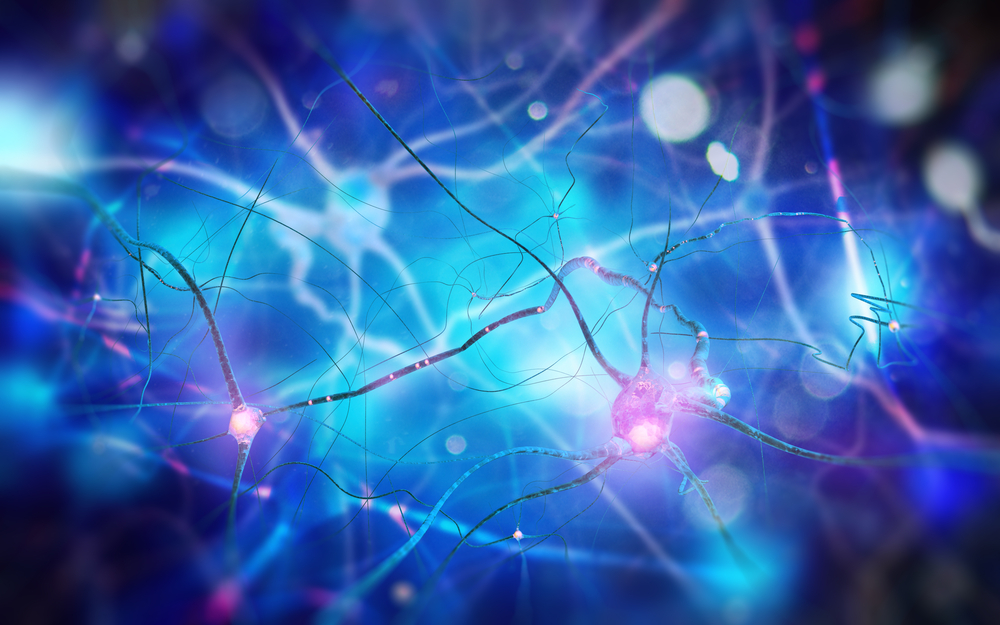

The accumulation and aggregation of specific proteins in nerve cells is a hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases. These aggregates are believed to be toxic and lead to the nerve cell death and neurodegeneration associated with those conditions.

In ALS, the main component of these toxic aggregates is TDP-43, a RNA-binding protein that regulates RNA — a molecule generated from DNA that serves as a template to the production of a specific protein.

Ataxin-2, a RNA-binding protein implicated in the neurodegenerative disease spinocerebellar ataxia-2 (SCA2), was found to form toxic aggregates in ALS and to enhance TDP-43 toxic aggregation.

A recent study showed that reducing ataxin-2 levels led to the reduction of TPD-43 aggregation and slowed down the development and progression of neurodegeneration in an ALS-mouse model, making ataxin-2 a potential therapeutic target for ALS.

Now, a collaborative work involving researchers from the Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience in Dublin, Ireland, the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute – University of Colorado in Boulder, investigated the mechanisms behind ataxin-2-associated neurodegeneration by focusing on a particular region of the protein.

The small area, known as the intrinsically disordered region (IDR), is thought to help ataxin-2 in the formation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules. These structures store RNAs in an inactive form until they are required to produce molecules.

Considering the association between ataxin-2 and neurodegeneration, the researchers investigated whether ataxin-2’s IDR — and indirectly, RNP granules — were involved in the neurodegenerative processes.

The genetic deletion of ataxin-2’s IDR in fruit flies prevented the formation of RNP granules and showed that this region is required for the stability and strength of ataxin-2 interactions with other cellular components, such as TPD-43, which naturally leads to aggregation.

This deletion was found to be sufficient to prevent nerve cell damage, as these genetically altered flies were highly resistant to neurodegeneration.

“This suggests the normal Ataxin-2 protein and its ability to form aggregates is required for the progression of at least some forms of [ALS],” Arnas Petrauskas, one of the study’s authors, said in a press release.

To the researchers’ surprise, the deletion of ataxin-2’s IDR also affected the flies’ long-term memories, but not their short-term memories.

Since long-term memories depend on complex mechanisms that rely on the local regulation of RNA in nerve cells, ataxin-2 seems to be have a key role in the binding of several RNA-binding proteins involved in this process. However, in doing so, ataxin-2 creates a favorable environment for the formation of toxic aggregates between those proteins.

The study revealed that this region promotes the development of long-term memory and, paradoxically, of toxic aggregates that lead to neurodegeneration.

A possible explanation would be that the mechanisms behind the formation and degradation of RNP granules are tilted toward granule accumulation in diseased conditions, according to Baskar Bakthavachalu, the study’s co-first author.

The authors of a commentary published in the same issue of the journal noted that these findings “suggest that manipulating RNP granule formation by genetically manipulating ataxin-2’s IDRs, or by other means could be therapeutic in ALS,” and that the “race is now on to discover additional proteins that help build RNP granules.”