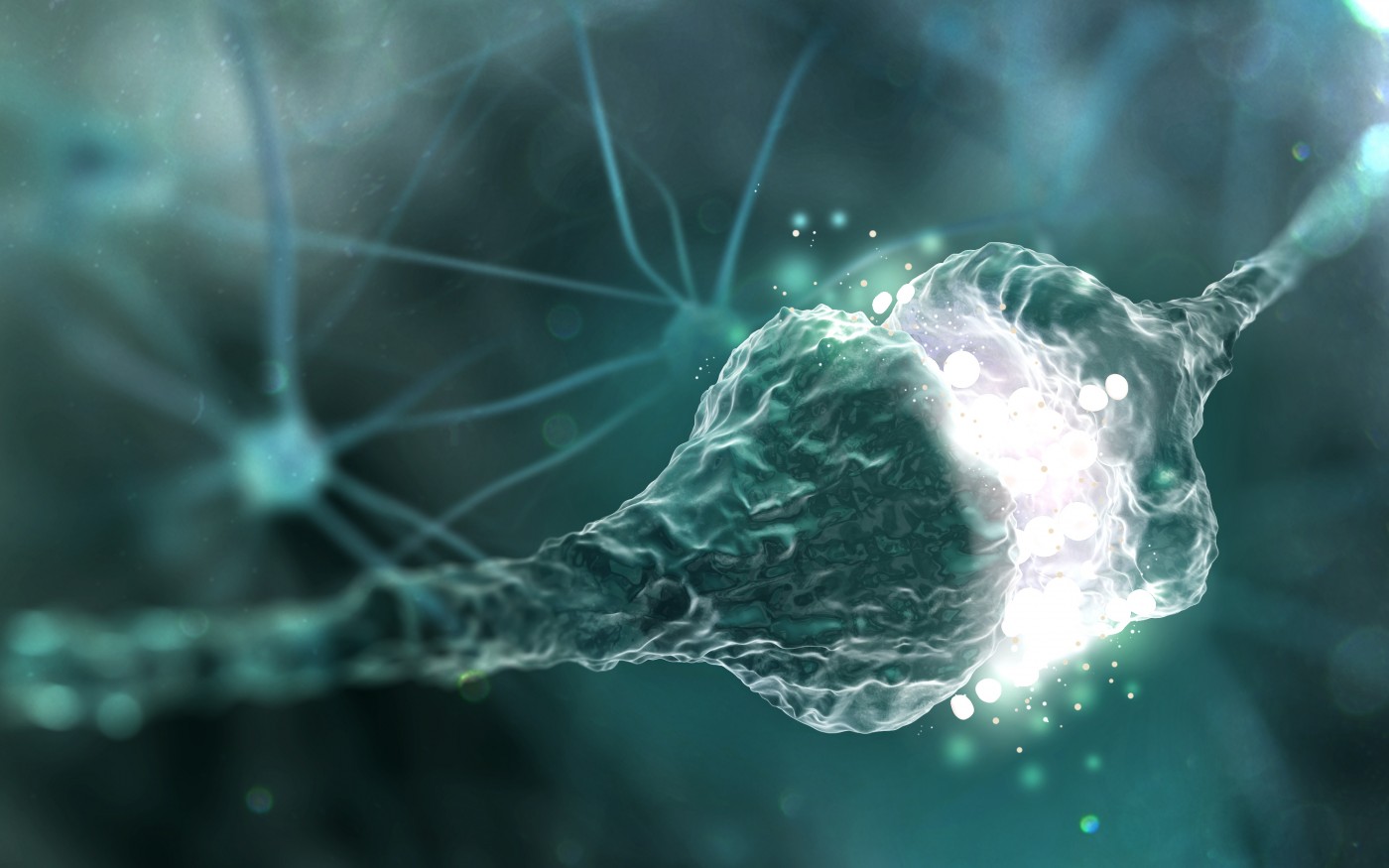

Neuron Death in ALS May Be Triggered by Increased Toxic Excitatory Nerve Signaling

Written by |

Increased excitatory toxic signaling in neurons in the part of the brain controlling movement triggers the breakdown of cells long before any symptoms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are noticed — at least in mice with ALS.

The study, “Cortical synaptic and dendritic spine abnormalities in a presymptomatic TDP-43 model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” published in the journal Scientific Reports, suggests that the detrimental signaling is linked to abnormalities in the TDP-43 protein.

About 95 percent of all ALS patients have aggregates of the TDP-43 protein in their nerve cells, and mice carrying mutations in the gene coding for the protein are used to model ALS. Other studies have also suggested that neurons in ALS patients may be overactive.

Neurons are often grouped into those that propel excitatory signals, urging other cells to act, or inhibitory signals, which prevent other cells from acting.

When neurons, which use the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, become hyperactive, the increase in signaling becomes toxic to the cell. Such hyperactivity, which researchers refer to as excitotoxicity, is known to kill neurons.

With these facts in mind, the research team from the University of Queensland in Australia explored how mutations in TDP-43 affect nerve signaling in mice. Mice carrying a mutation in TDP-43 develop ALS-like disease, but the team focused on mice at an earlier age — adult, but not yet developing symptoms.

The team found that excitatory neurons in the motor cortex of mutated mice signaled at a 148 percent higher rate than in normal mice. There was no difference in inhibitory signaling between the mice, indicating there was a severe imbalance between activating and inhibiting signals.

They also discovered that the mutated mice had a 53 percent increase in the density of dendritic spines. Dendritic spines are tiny protrusions from the surface of the dendrite, or input branch, of a neuron. They show synapses in which a cell receives input signals, and can be compared to the microphone where you order fast food at a drive-through.

But simply observing the spines did not tell researchers if they were active or not. So the team compared the number of spines, or microphones, to the observed excitatory signaling — or the amount of orders actually processed in the kitchen.

The analysis showed that the more spines, the more the cells signaled. This was true for both normal and mutated mice, and provided support for the idea that increased excitatory signaling may be what triggers neuron death in ALS.

The team also reported that both male and female mice had the same type and degree of changes.