Rare Variants in TET2 Gene May Double Person’s Risk of ALS, Similar Ills

Rare variations in the TET2 gene seem to double a person’s risk of multiple neurodegenerative diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and Alzheimer’s disease, according to a recent study.

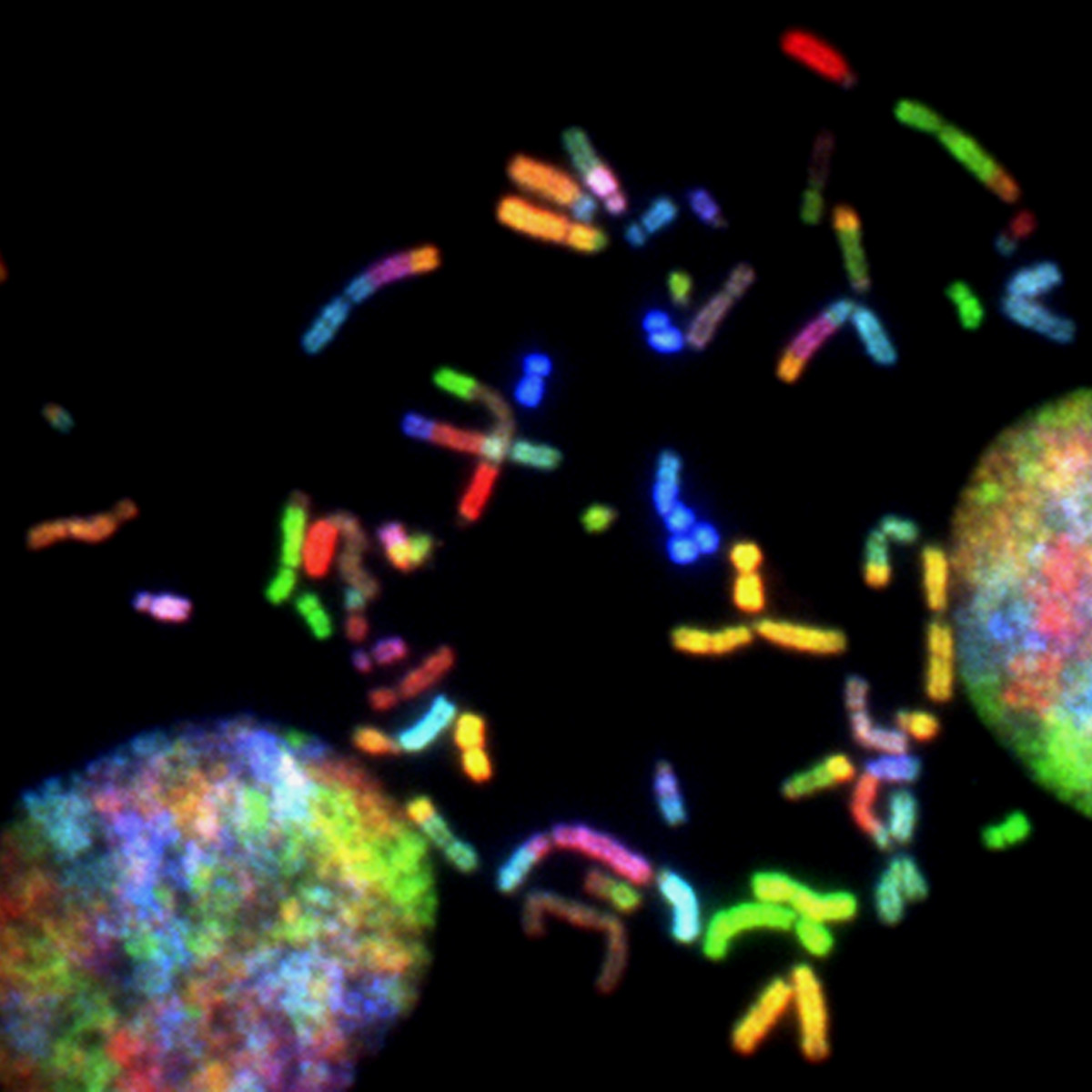

This gene codes for a protein involved in removing small chemical groups from DNA that influence how it is read. These signals are also affected during aging, suggesting that these genetic changes may affect critical aging-related processes in the brain.

The research, “Non-coding and Loss-of-Function Coding Variants in TET2 are Associated with Multiple Neurodegenerative Diseases,” was published in the American Journal of Human Genetics.

Multiple genes are implicated in the onset and development of neurodegenerative disorders. But known genetic variants — differences in DNA sequences that influence a person’s characteristics, like hair and skin color, or disease susceptibility — are still far from explaining a disorder’s inheritance pattern. This difficulty suggests that genetic factors yet to be discovered are likely playing a part.

More than 20 different genes have been associated with ALS, but rare genetic variants appear to be the greatest contributors to the disease. Some of these rare variants might also be common to a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, explaining the partial overlap between some of them.

Researchers at the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), set out to identify new genetic variants in people with neurodegenerative diseases.

They examined the genomes of 1,106 individuals of European ancestry, including 493 people with either Alzheimer’s, ALS, or FDT, and 671 healthy people serving as controls. Most of the patients had early onset disease (before age 65), making it more likely a genetic factor would be associated with their disorder.

The analysis retrieved only one gene whose variations were significantly linked to disease: the TET2 gene. These variations were found both in coding regions of the gene — those that directly code for protein components — and in non-coding regions, mostly in those that regulate how much of the gene is produced.

“We didn’t go in with any suspicions about what we might [get], so we’re excited that we did find a new genetic association here,” Nicholas Cochran, PhD, the study’s first author and a senior scientist at HudsonAlpha, said in a press release.

The team then validated its findings across more than 16,000 patients and 15,000 controls using different databases. Again, rare TET2 variations were significantly more common in neurodegenerative disease patients, and were found to increase the risk for these diseases by nearly twofold.

Specific variations in this gene that resulted in the loss of the TET2 protein increased this risk by three times, the team noted.

Rare TET2 variants were also associated with faster cognitive decline in patients already showing with mild cognitive decline, suggesting that these gene variants were accelerating disease progression.

“We identified a significant excess of rare, likely deleterious variation in TET2 as a risk factor for multiple neurodegenerative disorders, including [Alzheimer’s], FTD, and ALS,” the researchers wrote.

“Finding evidence for a risk factor that contributes to multiple neurodegenerative diseases is exciting,” said Richard M. Myers, PhD, HudsonAlpha’s president and science director. “We already know that these diseases share some pathologies. This work shows that the underlying causes of those pathologies may also be shared.”

The TET2 protein is involved in DNA demethylation — or in removing chemical groups (methyl) from the DNA that changes how it is read. This means that patients with TET2 genetic variations likely have more DNA methylation than those without these variations.

Notably, studies have suggested that DNA becomes more methylated — that is, it has a lot of these chemical groups — as we age, with aging known to increase a person’s risk of disease. The recent findings suggest that TET2 genetic variations accelerate these aging processes, putting people at higher risk of neurodegenerative disorders.

“Sometimes we get a hit, and it’s hard to understand what it might be doing, but TET2 already has established roles in the brain. So this finding really made sense,” Cochran added.

Additional research is now needed to uncover how changes in TET2 levels or activity contribute to disease, and whether this gene might increase a person’s risk for other age-related disorders.