Riluzole and blood sugar-boosting diet interact to slow ALS: Study

High glycemic index diet linked to slower declines in patients on riluzole

Written by |

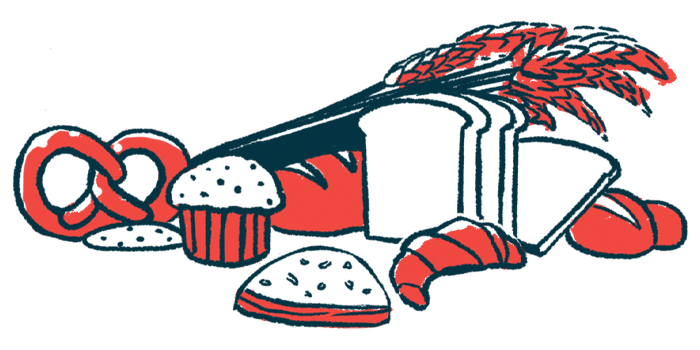

A diet containing foods that quickly raise blood sugar is associated with slower amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) progression in people taking the standard treatment riluzole, according to data from a recent study.

Scientists had previously found that a high glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) — two measures that account for the way foods influence blood sugar levels — were associated with slower ALS progression. Their data now showed these effects were stronger among the group of patients who were also taking riluzole.

Given the observed relationship, “nutritional counseling and dietary modification might help maximize the benefit of this drug,” researchers wrote.

The study, “Interaction between riluzole treatment and dietary glycemic index in the disease progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” was published in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology.

ALS is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by worsening muscle weakness that causes patients to lose their ability to perform day-to-day functions.

Researching nutritional interventions that may be able to slow ALS progression

It’s believed that an appropriate diet is important to help ALS patients maintain their health for as long as possible, but research is still ongoing as to whether any particular nutritional interventions or dietary components may be able to slow ALS progression or help patients live longer.

In a previous study involving 304 sporadic ALS patients from the ALS Multicenter Cohort Study of Oxidative stress (COSMOS), the researchers found patients who ate foods with a higher GI or GL exhibited slower disease progression. A higher GI was also linked to better survival.

GI is a measure of how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food will increase a person’s blood sugar, with a higher GI reflecting a faster blood sugar spike. GL takes into account GI and the total number of carbohydrates consumed. Carbohydrates are the nutrients that are broken down into sugar (glucose) to produce energy in the body. They’re found in sugary and starchy foods like fruits, grains, and potatoes.

In a response to the study, another scientist raised the question as to whether riluzole treatment may have influenced the observed relationships between GI/GL and disease progression.

Riluzole is an approved therapy that’s been shown to have a modest survival benefit in ALS. It comes in various formulations, including oral tablets (Rilutek), liquid suspension (Tiglutik), and a film dissolved on the tongue (Exservan).

The treatment is believed to work by blocking signaling of glutamate, a brain chemical that can be toxic to nerve cells when in excess. Some data suggest riluzole may also influence glucose transport or metabolism.

To further examine this possible relationship, the researchers performed a new analysis of the COSMOS data. As in the previous report, participants had completed a food frequency questionnaire at the study’s start (baseline) and their disease progression was monitored with the ALS Functional Rating Scale – Revised (ALSFRS-R).

Among the 304 participants, 53% reported using riluzole at baseline and 47% did not. No significant association between riluzole treatment and ALSFRS-R score declines was seen in the first three months.

GI and riluzole interacted to influence disease progression

Still, GI and riluzole interacted to influence disease progression. Basically, the previously observed relationship where a higher GI diet was linked to slower ALSFRS-R declines over three months of follow-up was also seen in the riluzole group, but not in those who weren’t taking the oral therapy at baseline. A similar association was observed when evaluating GL, riluzole, and disease progression.

In the riluzole group, the 25% of people with the lowest dietary GI exhibited a steeper decline in ALSFRS-R scores over three months than patients with higher GIs. Likewise, the 25% of people with the lowest GL showed faster functional declines than the 25% of people with the highest GL. These relationships weren’t observed in the group of people not on riluzole.

When modeling ALSFRS-R progression over six months or two years, there was again evidence that GI was linked to slower functional declines only among those on riluzole.

No significant interactions were observed between GI or GL and riluzole on survival alone, but in combined outcome analyses considering ALSFRS-R declines and survival, both a higher GI and GL were associated with better outcomes after three months, but not at later periods, among those on riluzole.

According to the team, the findings overall “suggest that riluzole and a high GI/GL diet might reduce functional decline synergistically in the early disease course.”

While the mechanisms underlying this association remain unknown, the researchers believe it could be related to effects on glucose and energy metabolism. They noted, however, that interpretation of the findings is limited by the observational nature of the study.

“A randomized controlled trial incorporating a biomarker such as continuous glucose monitoring is needed to decisively examine the impact of dietary glucose in ALS,” they wrote.