Scientists grow specialized motor neurons to aid in ALS research

Lab-grown cells mimic nerve cells lost in ALS, spinal cord injury

Written by |

- Scientists grew specialized motor neurons, lost in ALS and spinal cord injury.

- This new method uses brain progenitor cells to create corticospinal-like neurons.

- These lab-grown cells may aid ALS disease modeling and regenerative therapies.

Scientists have developed a way to grow motor neurons, the highly specialized nerve cells that are lost in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), opening the door to new research avenues for treatment discovery.

The new approach directs rare adult brain progenitor cells to become corticospinal-like neurons, a type of nerve cell that extends from the brain to the spinal cord and is essential for voluntary movement. These cells are particularly vulnerable in ALS and traumatic spinal cord injury.

The study, ”Directed differentiation of functional corticospinal-like neurons from endogenous SOX6+/NG2+ cortical progenitors,” was published in eLife.

“We have identified a subset of cortical progenitor cells with strong potential to differentiate into specialised neurons for disease modelling in ALS and spinal cord injury, and for regenerative therapies,” Jeffrey Macklis, MD, a professor at Harvard University and the study’s lead author, said in a journal press release.

A new way to model disease

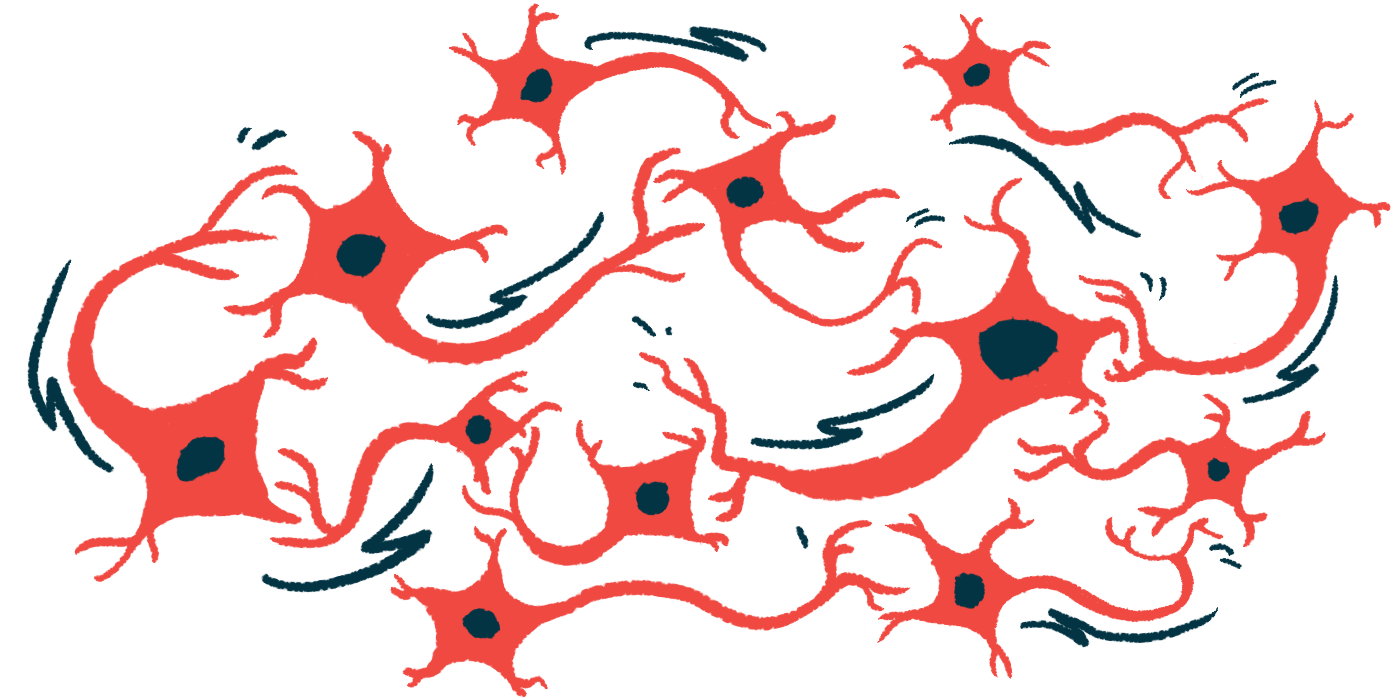

The nervous system contains many types of nerve cells, each with its own shape, location, connectivity to other nerve cells, and electrical activity. Corticospinal neurons, or upper motor neurons, connect the motor cortex in the brain to the spinal cord, transmitting signals that enable voluntary movement and fine motor control.

A loss of these cells impairs voluntary movement, as seen in ALS. However, no cell-based models of corticospinal neurons exist, which limits the investigation of their selective vulnerability and degeneration in ALS, as well as the development of new strategies to regenerate them following spinal cord injury.

“To realistically model diseases and screen for potential treatments, or to regenerate neurons that are damaged in spinal injuries, we need reliable approaches to accurately differentiate progenitor cells into these specific types of neurons,” said co-first author Kadir Ozkan, PhD, who was a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard at the time the study was conducted. “Generic or regionally similar neurons do not adequately reflect the selective vulnerability of neuron subtypes in most human neurodegenerative diseases or injuries.”

To develop an appropriate cell-based model, the researchers first identified a specific population of stem-like progenitor cells in the mouse brain that produce the regulatory molecules Sox6 and NG2. Sox6 normally prevents these cells from becoming neurons.

“Knowing that a subset of early progenitors and glial [support] cells in the cortex share a common ancestry with cortical ‘projection neurons’, we hypothesised that some of these progenitors might retain dormant neurogenic potential – that is, the potential to differentiate into neurons,” said co-first author Hari Padmanabhan, PhD, who was also a postdoctoral fellow at the time of the study. “We wanted to grow these cortical SOX6+/NG2+ progenitors in the lab and see if we could direct their differentiation into corticospinal neurons.”

After isolating these cells, the researchers developed a way to precisely control the activity of three key developmental genes: Neurog2, VP16:Olig2, and Fezf2. This technique successfully directed progenitor cells to become corticospinal-like neurons.

These lab-grown neurons closely matched their natural corticospinal neuron counterparts in structure, gene activity, and electrical activity. This contrasted with the standard method for differentiating nerve cells, which activated Neurog2 alone and yielded abnormal or mixed neuron types.

“Importantly, SOX6+/NG2+ progenitor cells are widely distributed in the cortex, already positioned near sites of degeneration,” Macklis said. “This adds substantially to their therapeutic potential, pending further study.”