Stem cell-based therapy deemed safe in Phase 2 study

Treatment with CL2020 was tolerated well by five people in Japanese trial

CL2020, a stem cell-based therapy that was being developed by the Life Science Institute, part of Mitsubishi Chemical, was found to be safe and tolerated well by five people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) who took part in a Phase 2 clinical study.

The investigational therapy, which involved repeated injections of a special type of stress-enduring stem cells, known as Muse cells, directly into the bloodstream, also tended to improve physical function for these patients, but not significantly so.

Because the study included only a small number of patients, “a double-blinded study including a larger number of ALS patients with a longer observation period should be conducted,” the researchers wrote.

In February 2023, however, Mitsubishi had already decided to discontinue the development of CL2020 “after comprehensive and careful consideration of the latest clinical developments, timelines for commercialization, and its pharmaceutical business strategy going forward,” the company stated in a news release.

The study, “Safety and Clinical Effects of a Muse Cell-Based Product in Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Results of a Phase 2 Clinical Trial,” was published in Cell Transplantation.

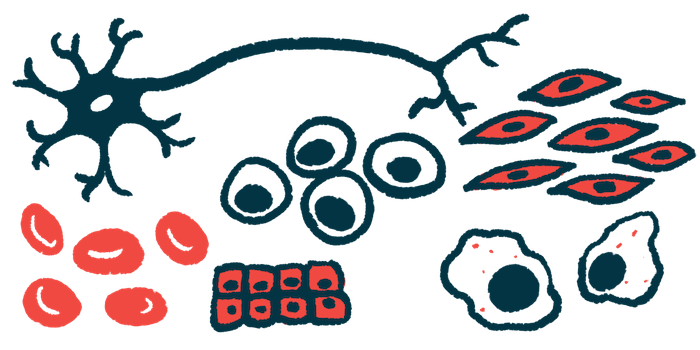

ALS is a progressive disease that causes the loss of motor neurons, the nerve cells that control voluntary muscles in the body, leading to muscle weakness and atrophy (shrinkage) and a range of other symptoms.

The exact causes of ALS are unclear, but inflammation triggered by astrocytes is believed to contribute to disease progression. Astrocytes are star-shaped cells found in the brain and spinal cord that are needed to maintain healthy motor neurons.

Stem cells’ roles in treating ALS

Stem cells may have a role to play in treating ALS, either by delivering growth factors to motor neurons, by replacing lost motor neurons with new ones derived from stem cells, or by providing a source of healthy astrocytes to support motor neurons.

Unlike other types of stem cells, it is believed that Muse cells, when injected into the bloodstream, tend to travel to damaged tissue, survive in hostile environments, and naturally develop into any type of cells compatible with the surrounding tissue.

They can be found in the connective tissue of nearly every organ, and do not take very long to collect. A preclinical study in a mouse model of ALS showed that Muse cells can turn into astrocytes, help motor neurons survive, and prevent muscle atrophy.

Now, a team of researchers in Japan led an open-label clinical study (jRCT2063200047) testing the safety and efficacy of Life Science Institute’s CL2020, a Muse cell-based product derived from bone marrow human mesenchymal stem cells. These cells have the ability to transform into various cell types, such as bone, fat, and cartilage cells, and play a crucial role in tissue repair and regeneration.

The study included three men and two women, ages 45 to 68 years, with a diagnosis of ALS. Three were receiving treatment with riluzole, sold as Rilutek among others.

As part of the study, they received a total of six intravenous (into-the-vein) injections of clinical-grade CL2020 administered at one-month intervals. Each dose of CL2020 contained 15 million Muse cells.

Study goals

The study’s main goal was to assess the treatment’s safety and tolerability. Over 12 months (one year) following the first dose, a total of 28 side effects were reported. The most common side effects were headache (four cases) and fatigue (three cases).

However, there were no treatment-related serious side effects and no changes in the patients’ vital signs or lab test results. “Treatment was highly tolerated without serious side effects,” the researchers wrote.

As a secondary goal, physical function was measured using the ALS Functional Rating Scale Revised (ALSFRS-R), where lower scores indicate more impaired physical function.

While ALSFRS-R scores were a mean three points lower at 12 months than at the beginning of the study (37.6 vs. 40.6 points), the rate of change over the 12-month window showed only a trend toward improvement.

“The difference was not statistically significant,” the researchers wrote. “Among five patients diagnosed with ALS, three exhibited a decrease in the rate of ALSFRS-R score change, one demonstrated an increase, and another showed no change.”

Neurofilament light chain (NfL) levels

Blood levels of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, two inflammatory molecules, increased over the course of the study. Neurofilament light chain (NfL), a marker of nerve cell damage, increased in cerebrospinal fluid, the liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

However, the levels of NfL “were relatively lower than those of ALS natural history patients,” indicating that patients in the study possibly had “a relatively slow rate of disease progression.”

Blood levels of sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P), a molecule that guides immune cells to sites of inflammation, decreased over the course of the study. Targeting S1P signaling with Gilenya (fingolimod), a medication approved for multiple sclerosis, is being tested in ALS.

“Considering the results of clinical scores, including the ALSFRS-R, and the biomarker findings mentioned above, it can be concluded that CL2020 treatment alone may have slowed down ALS progression but was not fully capable of halting it,” the researchers wrote.