With Likely Diagnosis, Target ALS Founder Refocuses

Portrait photo of Daniel Doctoroff. (Photo courtesy of Daniel Doctoroff)

Note: This story was updated Jan. 25, 2022, to clarify that Target ALS has raised $90 million since its inception in 2010.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) has been a part of Daniel Doctoroff’s life for more than two decades.

His father, Martin Doctoroff, died of the disease in 2002, and ALS claimed his uncle Michael Doctoroff some eight years later, in 2010. The same year, he founded the research-focused organization that would later be known as Target ALS.

Now, after being immersed in ALS for so long, he must embrace a whole new perspective — his likely diagnosis with the disease.

“When you confront a sort of existential moment, your priorities become really clear. And I have no trouble making those choices,” Doctoroff, 63, said in a video interview with ALS News Today.

That meant stepping down as CEO of Sidewalk Labs, Alphabet’s urban innovation company, effective Jan. 31. Doctoroff wants to spend more time with family, focus on his health, and try to find a cure for the disease through his foundation, Target ALS.

“I’m going to do whatever I can to prolong this as long as possible, and do as much good along the way as I can,” Doctoroff said from his home in New York City.

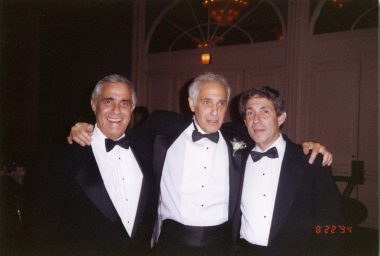

From left: Martin, Michael, and Steve Doctoroff in 1994. (Photo courtesy of Daniel Doctoroff)

Doctoroff publicly announced his likely ALS diagnosis and retirement from Sidewalk Labs in December. In that piece, the former Bloomberg CEO and president, who also served as a deputy mayor of New York City, wrote about hip weakness that started two years ago. It grew progressively worse and prompted him to seek out top ALS specialists. They determined he probably had the neurodegenerative disease.

There is no one test that diagnoses ALS. Rather it requires a host of tests, including blood work, a lipidomics study (how fuel for mitochondria is processed in motor neurons), and studies of pulmonary function, nerve conduction, and genetics.

Doctoroff said his results to date line up in fairly similar ways to those of ALS patients. He tested negative for the familial mutation that caused his father and uncle’s disease, but that does not rule out non-genetic causes or a second unidentified gene in the family.

Doctoroff has begun a cocktail of medications that he hopes will slow the hallmark neurological progression of ALS. That includes riluzole (marketed as Rilutek, Tiglutik, and Exservan), TUDCA (tauroursodeoxycholic acid), and sodium phenylbutyrate.

While a likely ALS diagnosis is difficult news for anyone to absorb, Doctoroff is set on continuing with a positive mindset and focusing on what he has — family and a full life experience.

“I’ve had some great friends and a wonderful family. I got to do professionally what I wanted to do. I’ve had outside interests that have mattered to me. And I feel very lucky and have no regrets,” said Doctoroff, who has been married for 40 years and has three adult children, two of whom were married in 2021, and a 2-month-old granddaughter.

Target ALS is focus

Scaling up Target ALS, the collaborative organization he started out of Columbia University in 2010 (the name Target ALS came in 2013), is next on Doctoroff’s list of priorities. To date, according to Doctoroff, it has raised $90 million for academic and industry groups studying ALS, and for scientific resources to aid more than 600 projects worldwide.

CEO Manish Raisinghani, PhD, said the Target ALS model focuses on the overlap between discoveries in academia and the bench-to-bedside expertise of the biotech industry to bring new treatments and a better understanding of underlying disease mechanism. He describes Target ALS as the glue that binds these two worlds.

Sometimes Target ALS provides funding to these consortia. Other times, it serves as a connector between multiple researchers who each are working on complementary parts of a particular problem with ALS or treatment. The foundation has spent approximately $58 million between these collaborative groups and developing its own scientific resources, such as genomic data sets, animal models, and viral vectors, Raisinghani said.

ALS is “a complex puzzle that is thrown at us by nature,” Raisinghani said. “And in my view, no complex problem is going to be solved by a single individual.”

For example, Raisinghani points to a 2013 consortium that Target ALS funded that was focused on figuring out the biology of the newly identified C9orf72 gene. The seven-person scientific group found that the mutated gene was responsible, in part, for the abnormal transfer of proteins between the nucleus and cytoplasm (fluid surrounding the nucleus of the cell).

It so happened that an oncology-focused company, Karyopharm, was looking at the same pathway to treat lung cancer with a potential therapeutic called KPT-350. That program, now called BBIIB078, was bought by Biogen and clinical trials for it in ALS commenced in 2019. The second round of the Phase 1 study (NCT03626012) was completed in November.

Leveraging diverse expertise from people within and outside the ALS scientific community has proven successful for the small nonprofit. Since 2013, 60% of Target ALS’ consortia have led to continuing drug discovery programs and six clinical trials in ALS. Doctoroff said that’s been done with a budget of about $9 million per year since 2014.

More recently, Target ALS and the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation partnered to fund from six to 10 biomarker-based projects over the next two years.

This collaborative spirit is what Raisinghani said Doctoroff brought to Target ALS when it was just forming and continues to emphasize, especially now.

“Nowhere … in our name, or any of our programs, do you hear Dan’s name,” Raisinghani said. “And that’s intentional, and that I think reflects his remarkably understated approach to not putting himself up front.”

As the founder of Target ALS, Doctoroff does not become involved in the science. However, he brought his public and private sector experience to the center of the organization’s governance structure. All funding decisions are made through a peer review process, Raisinghani said. Half of that independent review committee is made up of academic scientists and half of industry scientists. None take grant money from Target ALS.

Goals and plans

Doctoroff said he intends to continue on this path, but add more funds for the organization to leverage. He’s made a lofty goal for himself to raise $250 million. He said his personal ALS story, paired with an economic incentive to find treatments for this disease, will make a difference.

“Not only is that a massive contribution to mankind, but they [biotech companies] can also earn a return on their investment in the clinical trials and ultimately, hopefully, successful clinical trials and the creation of the medication,” Doctoroff said.

There’s plenty more he would like to experience with the time he has. In his announcement about stepping down from Sidewalk Labs, he mentioned learning to speak French fluently and reading more books “just for pleasure.” Doctoroff said he and his wife, Alisa, are planning a trip to Sweden to see the northern lights. It’s something they’ve always wanted to do.

“Already the adventures are beginning,” Doctoroff said.

Doctoroff recalled a story about his late uncle Mike. Though he was in a wheelchair and couldn’t speak because of ALS, he enjoyed life up until the end.

Doctoroff said his uncle participated as much as he could in his grandson’s bar mitzvah three weeks before he died. He held up funny signs in the Jewish rite of passage and celebration that marks a boy’s 13th birthday. “I will never forget the joy on his face,” Doctoroff said.

That’s what he’s focusing on in this new chapter of his life. “I go into this optimistic and positive, and determined to — whatever it is — make the best of it.”