ALS/MND 2023: Blood sugar-boosting diet may slow ALS progression

Such a diet also may prolong survival, symposium presenter suggests

Written by |

Eating foods with a higher glycemic index — those more likely to quickly raise a person’s blood sugar — is associated with slower functional declines and prolonged survival among people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), according to a recent analysis.

Foods with high amounts of sugar include white bread and rice, while foods such as oatmeal, lentils, or kidney beans have a low glycemic index, resulting in lower blood sugar peaks but sustained sugar levels for longer periods.

Ikjae Lee, MD, of Columbia University in New York, presented the data in an oral presentation, “Higher Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Diet is associated with Slower Disease Progression in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis,” at the 34th International Symposium on ALS/MND, being held Dec. 6-8 in Basel, Switzerland. The findings also were published recently in a study in the Annals of Neurology.

“Dietary [glycemic index] is associated with functional decline and survival in ALS,” Lee said in the presentation, noting a need for more studies to confirm this relationship.

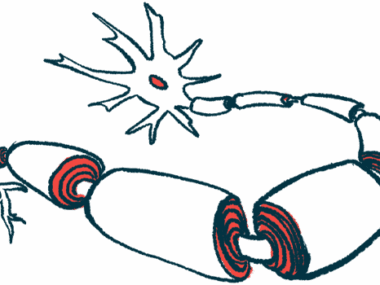

In ALS, degeneration of the nerve cells involved in muscle control causes weakness in the muscles needed to walk and speak, but also those needed to eat and drink. Difficulty swallowing food can lead to malnutrition and weight loss, which have been linked to a worse prognosis among ALS patients.

As such, an appropriate diet is thought to be important for helping patients maintain their health for as long as possible.

Studies have suggested that a diet high in calories could help to slow the neurodegenerative disease and help patients live longer, although most studies have been small and the findings sometimes conflicting.

It hasn’t been established whether there is a nutritional intervention that might be of benefit for a broad ALS population, Lee noted. Moreover, it is not known which specific dietary components (macronutrients) — such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins — might be most important for influencing ALS progression, and if their effects on blood sugar play a role.

The ALS Multicenter Cohort Study of Oxidative Stress

In the study, researchers examined the possible relationship between dietary components and ALS progression and survival among a group of 304 ALS patients in the U.S. involved in the ALS Multicenter Cohort Study of Oxidative Stress (COSMOS).

Participants — 59% men and 41% women — had a mean age of 61.6 and had experienced their first ALS symptoms less than 1.5 years prior to enrollment.

Dietary intake was assessed with a food frequency questionnaire at the study’s start (baseline). Disease progression was monitored using the ALS Functional Rating Scale — Revised (ALSFRS-R).

Initial analyses adjusting for age and sex indicated that higher caloric intake and greater fat consumption were linked to slower functional declines. But these findings failed to reach statistical significance in final analyses where the team also accounted for clinical factors such as disease duration, disability levels, respiratory function, and initial symptoms.

However, “this is an observational study,” Lee noted. “We would not conclude that there is no association … just with our data.”

Measuring glycemic index and glycemic load

Meanwhile, the glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) of participants’ diets were associated significantly with ALS progression at a three-month follow-up in adjusted analyses.

GI is a measure of how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food will increase a person’s blood sugar (glucose). Carbohydrates are the nutrients that are broken down into glucose to produce energy. In turn, GL takes into account the glycemic index and the total number of carbohydrates in a serving of that food.

For each one-unit increase in GI, reflecting a faster blood sugar spike, patients saw a 0.13-point slower ALSFRS-R decline. The 25% of participants with the lowest GI also experienced significantly faster ALSFRS-R score progression relative to the other participants.

Likewise, for every unit increase in GL, ALSFRS-R declines were 0.01-points slower, and the 25% of patients with the lowest GL also experienced a significantly faster decline in ALSFRS-R scores than the remaining participants.

Higher GI also was tied significantly to slower ALS progression after six months, a finding the scientists validated in another group of ALS patients.

Finally, survival analyses indicated that the 25% of patients with the lowest GI had the shortest survival relative to the other patients, “about eight months shorter than the other group,” Lee said. In final adjusted analyses, a higher GI also was associated with longer survival without the need for a tracheostomy, or breathing tube placement.

Preventing protein misfolding may slow ALS progression

Mechanistically, the scientist believes a higher glucose-based diet could help slow disease progression by preventing protein misfolding. Misfolded proteins are known to toxically accumulate in the patients’ brains, where they’re implicated in ALS progression.

Lee emphasized, however, that the observed relationship between GI and disease progression “does not confirm causation.”

“Now, that being said, I really believe in our data,” the researcher added, noting that when looking at individual high-carb food items, such as French fries, spaghetti, or macaroni and cheese, greater intake of each of these foods also appeared linked to slower functional declines.

To confirm these relationships, “ultimately we need an interventional trial focusing on providing a higher GI diet or supplement,” Lee concluded.