ALS Patients with Emotion Recognition Problems May Improve with Positive Social Contact, Study Finds

Written by |

Researchers in a recent amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) study found that patients had problems reading negative emotions in other people because of changed activity in brain regions associated with emotional recognition. Conversely, patients with more frequent social contacts were able to neurologically compensate.

The study, “Perception of emotional facial expressions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) at behavioural and brain metabolic level,” was published in PLOS one.

A previous study revealed that patients with ALS have trouble understanding emotions in others and suggested that the problem may be caused by microscopic changes in the brain.

The new research explored the mechanism behind the problems using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) on the brains of patients with ALS in comparison to healthy subjects. The imaging technique measures activity by detecting blood flow in the brain because blood flow increases in areas that are in use.

Thirty patients with ALS and 29 without ALS participated in an emotion recognition task. Among them, 15 with ALS and 14 healthy subjects were additionally tested with fMRI. The participants were presented with pictures of faces expressing basic emotions of anger, disgust, fear, sadness, surprise, and happiness. All patients had at least six months between their diagnosis and the test comparison with the matched healthy volunteers. They were also screened for depression, which may impact emotional processing.

ALS patients had problems recognizing the negative emotions of disgust, fear, and sadness. When investigated with fMRI, researchers saw decreased activity in the brain regions that normally process those emotions. Depression was found to a higher extent in the ALS patients who also had additional problems with recognizing angry and happy faces.

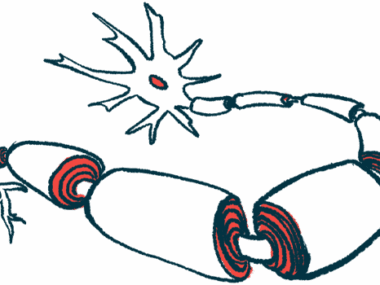

The team identified decreased activity in a brain area called the hippocampus, which is involved in memory retrieval. At the same time, increased activity was seen in the brain’s inferior frontal gyrus, which is associated with emotional imitating responses. The frontal gyrus harbors the so-called “mirror neurons” that are activated when infants respond to and mimic the emotional facial expressions of their mothers, including smiling or crying.

Based on the results, the team suggests that a compensating mechanism happens in patients with ALS. While healthy people use memory retrieval to correctly categorize emotional expressions, ALS patients may compensate for the deficit with increased activity in the part of the brain involved in imitating facial expressions.

The team noted that patients with the strongest activity in the frontal gyrus of the brain also had the highest frequency of social contacts. All findings considered, the study provides evidence of the importance of including ALS patients in social life.

“It has been suggested that social contacts are a protective factor against cognitive decline. Thus, neurodegenerative processes in the course of ALS might be counteracted by positive emotional activity in social life,” the researchers wrote.