Cancer Immunotherapy Aldesleukin Shows Promise for ALS in Pivotal Trial

Written by |

Low doses of Clinigen’s aldesleukin, an immunotherapy used in certain types of cancer, safely boosted the number and function of regulatory T-cells (Tregs), a type of immune cell that keeps others in check, in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), according to data from a pivotal Phase 2 clinical trial.

The results, which also showed a drop in the levels of a disease activity biomarker, highlighted aldesleukin’s potential to suppress excessive immune reactions and halt disease progression in ALS patients.

The study, “Repeated 5-day cycles of low dose aldesleukin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (IMODALS): A phase 2a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial,” was published in the journal Lancet EBioMedicine. It was conducted by a consortium of clinical and laboratory scientists from France, U.K., Italy, and Sweden.

Aldesleukin, originally developed by Novartis and now marketed by Clinigen under the brand name Proleukin, is an immunotherapy approved for treating certain types of cancer.

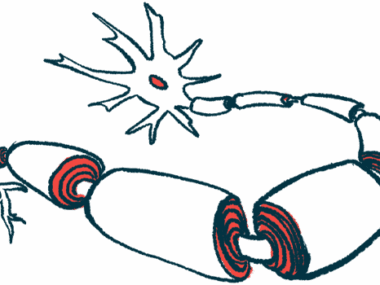

It is a lab-made version of interleukin 2 (IL-2), an immune signalling molecule known to play a key role in Tregs’ survival and function. Tregs act as negative regulators and shut down excessive immune and inflammatory responses triggered by other immune cells, maintaining a healthy immune balance.

Notably, a previous study showed that a shift toward an increase in pro-inflammatory immune cells in detriment of Tregs was linked with ALS severity and progression.

When administered at much lower doses than those used for cancer treatment, aldesleukin can boost Tregs’ numbers and function in people with certain autoimmune and inflammatory disorders. Therefore, low doses of aldesleukin may slow disease progression and lessen disease severity in ALS patients.

The pivotal, single-center, placebo-controlled, Phase 2 trial, called IMODALS (NCT02059759), was designed to evaluate the safety and effects of low-dose aldesleukin in 36 people with ALS.

Participants, recruited at the Montpellier Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Reference Centre, in France, were assigned randomly to receive an under-the-skin injection of either one of two doses of aldesleukin or a placebo, over five consecutive days every month, for three months. Patients were followed and evaluated for three months after treatment.

IMODALS’s main goal was to assess dose-related changes in the frequency, total numbers, and function of Tregs. Secondary goals included safety measures and changes in the levels of CCL2 and neurofilament light chain (NFL), two disease activity biomarkers, as well as in daily-life functioning — through the ALS functional rating scale.

Exploratory analysis assessed changes in signalling molecules associated with either pro-inflammatory or immunoregulatory functions in immune cells associated with ALS progression.

Participants’ mean age ranged from 54 to 57 years across the three groups and they had lived with the disease for about two years; 69% of them were men. Predefined assessments were performed in all patients, except for one who missed the last visit due to inability to travel.

Results showed that the trial met its primary goal, with both doses of aldesleukin resulting in a significant, dose-dependent, increase in Treg frequency and numbers, compared with a placebo.

This increase, sustained over one month after treatment, was accompanied with a boost in Tregs’ suppressive function, suggesting an improved ability to control the excessive immune responses that contribute to nerve cell damage in ALS.

Notably, patients in the placebo group showed a tendency “to lose either Treg frequency or function during the same timeframe,” the researchers wrote.

“This double benefit of ‘more Tregs’ and ‘better Tregs’ indicates that low dose [aldesleukin] therapy is fully functional in ALS patients,” Timothy Tree, MD, PhD, one of the study’s senior authors from the King’s College London’s School of Immunology & Microbial Sciences, said in a King’s College press release.

“Furthermore, this response was related to the dose of [aldesleukin], with higher levels of Tregs in the participants who received the higher dose,” Tree added.

In addition, aldesleukin treatment led to a significant increase in the levels of molecules associated with immunoregulatory functions, suggesting an overall shift toward immune suppression.

There also was a significant, dose-dependent drop in CCL2 levels, which are usually high in ALS patients. In contrast, while NFL levels showed an increase only in the placebo group, differences between groups were not statistically significant.

No significant differences were found in patients’ functioning between groups. The absence of such differences in participants’ NFL levels and functioning may be due to a large variability within groups and potential insensitivity of these measures to change over a short treatment period, the team noted.

Both doses of aldesleukin were well-tolerated, with most adverse events (side effects) being of mild-to-moderate severity and with no reports of treatment-related serious adverse events. Non-serious side effects, including injection site reactions and flu-like symptoms, occurred more frequently in the aldesleukin groups than in the placebo group.

These findings suggested that aldesleukin may safely have a “therapeutic impact on slowing ALS disease progression,” the researchers wrote.

The data supported the use of aldesleukin’s higher dose in the multicenter, placebo-controlled Phase 2 MIROCALS trial (NCT03039673), which is currently assessing the safety and effectiveness of 18 months of treatment with low-dose aldesleukin in 300 newly-diagnosed ALS patients.

MIROCALS is planned to end in September 2021, with results expected later that year.

Aldesleukin recently was granted orphan drug designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of (ALS).