Metabolic Changes Do Not Identify Who Will Develop ALS, Study Finds

Written by |

Although people who develop amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have altered levels of several blood metabolites — products of our cells’ metabolism — before disease onset, these changes do not enable reliable identification of who is at risk of having ALS, according to a large study.

The research, “Prediagnostic plasma metabolomics and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” was published in the journal Neurology.

Plasma metabolomics — the large-scale study of small molecules known as metabolites — may provide insight into ALS’ causes, as well as biomarkers to diagnose this disease before symptoms begin and when treatment may be more successful.

Most studies on metabolic changes in ALS have been small and led to inconsistent results. A 2014 study found that 32 metabolites identified patients with ALS with high specificity, but it remained unclear whether the reported metabolic alterations preceded diagnosis or reflected changes such as muscle atrophy (shrinkage).

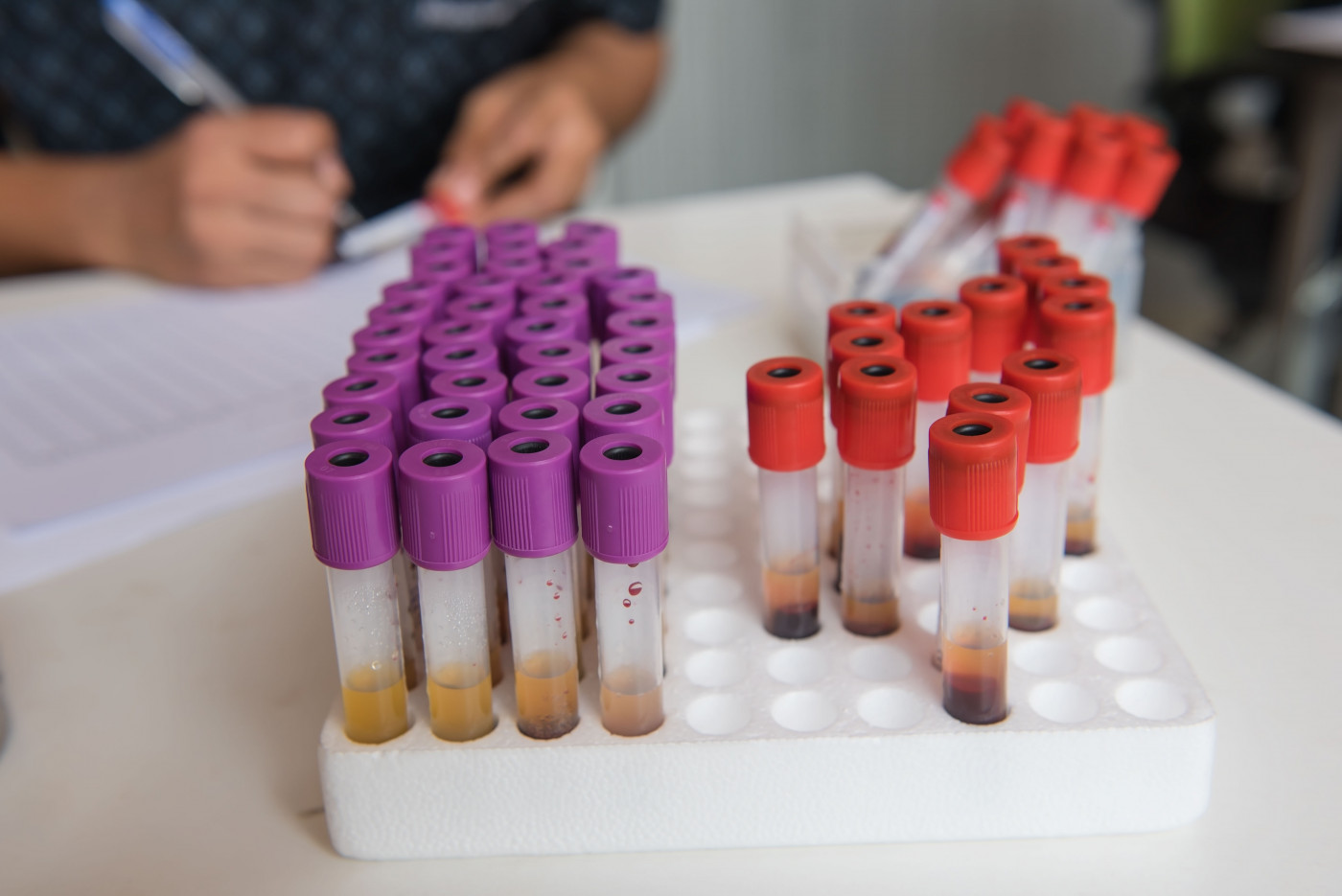

Aiming to determine if the metabolomic profile in healthy individuals may provide an indicator of their future risk of developing ALS, the team conducted a study including participants from five large studies in the U.S.: the Nurses’ Health Study, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort, the Multiethnic Cohort Study, and the Women’s Health Initiative.

The researchers identified 275 individuals (mean age 64.6 years, 200 women) who developed ALS during follow-up. Compared to the 549 controls, the people who developed ALS had a significantly lower body mass index.

The final 404 metabolites included in the analyses represent those identified with a technique called liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry that also passed the researchers’ quality control. Their association with ALS risk was evaluated through statistical analysis.

The first overall analysis showed that 31 molecules were associated with ALS risk, 27 of which were at lower levels in people who developed the disease than controls, and thus associated with lower ALS risk.

The results then showed that the number of metabolites with significantly different concentrations was higher when comparing controls to the 144 ALS cases with blood samples collected closer to disease onset than to the 131 with blood drawn five years or more before onset.

Specifically, in plasma samples collected within five years of ALS start, 63 metabolites — mainly lipids (fat), such as diacylglycerols and phosphatidylcholine — significantly correlated with lower ALS risk, and four with higher ALS risk. In turn, among those with blood drawn five or more years before ALS onset, 41 metabolites were linked significantly with ALS risk.

However, none of the metabolites remained significantly associated with ALS in subsequent analyses regardless of the interval between blood collection and ALS onset, although most of the molecules were at lower levels in the participants who developed ALS than in the controls.

Overall, “although the metabolomic profile in blood samples collected years before ALS diagnosis did not reliably separate presymptomatic ALS cases from controls, our results suggest that ALS is preceded by a broad, but poorly defined, metabolic dysregulation,” the scientists wrote.