North Carolina Study Could Lead to Better Gene Therapies for ALS

Written by |

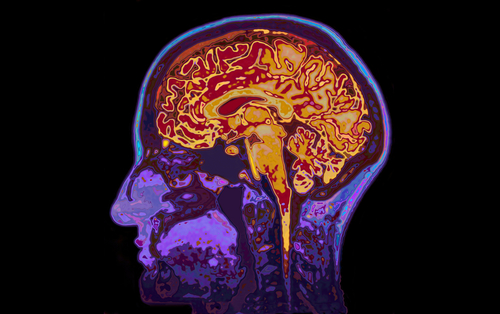

University of North Carolina researchers have identified the DNA sequence in a virus that lets it deliver treatments for neurodegenerative diseases to the brain.

The finding may pave the way for the development of improved and safer gene therapies for diseases like ALS, the team said.

A number of gene therapies for neurodegenerative disorders involve a non-infectious virus carrying treatments from the blood past the blood-brain barrier and into the brain. The barrier is a key natural protection against harmful invaders entering the brain.

The University of North Carolina School of Medicine team published its finding in the journal Molecular Therapy. The report was titled “Mapping the Structural Determinants Required for AAVrh.10 Transport across the Blood-Brain Barrier.”

“This structural ‘footprint’ we found seems to help these viruses get efficiently into the brain, which informs the design of potentially safer brain-targeted gene therapies,” Dr. Aravind Asokan, an associate professor of genetics who was senior author of the study, said in a news release.

More scientists see gene therapy as an attractive option for treating a broad range of genetic diseases. But many attempts have failed because the therapies were unable to pass the blood-brain barrier to get to the central nervous system cells where they need to go. In addition, high doses of the treatments have triggered harmful side effects.

The team decided to evaluate the structures of the harmless viruses used to deliver gene therapies — in particular adeno-associated viruses. They compared the structures of a type of virus that is unable to cross the blood-brain barrier with one that can reach the brain in mice.

At the heart of their work was creating a library with information on all of the DNA sequences in both types of virus. By swapping small sequences of DNA from one virus to the other, they were able to transform the virus that could not reach the brain into one that could.

A key finding was that the sequence that allows a virus to cross the blood-brain barrier consists of just eight amino acids on the virus’s coating.

“Grafting that structural footprint onto another AAV [adeno-associated virus] strain enables it to cross into the brain much more easily,” said Blake Albright, a graduate research assistant who was the lead author of the study.

When the team tested the tweaked version of the virus in mice, they discovered that not only did it reach the brain, but it had an affinity for nerve cells rather than other types of cells. The findings suggested that the engineered viral structure could lead to better targeting of nerve cells in the central nervous system and reduced toxicity.

The team is conducting additional studies to try to understand how the small DNA sequence leads to the virus being able to cross the blood-brain barrier. They are also studying whether different viral structures can help a virus cross animals’ blood-brain barrier.