Specialized Immune Cells May Help Slow ALS Progression, Study Shows

Written by |

Higher levels of a specialized type of immune cell may help halt the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a study in humans and mice found.

These findings were reported in the journal JAMA Neurology, in the study, “Association of Regulatory T-Cell Expansion With Progression of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.”

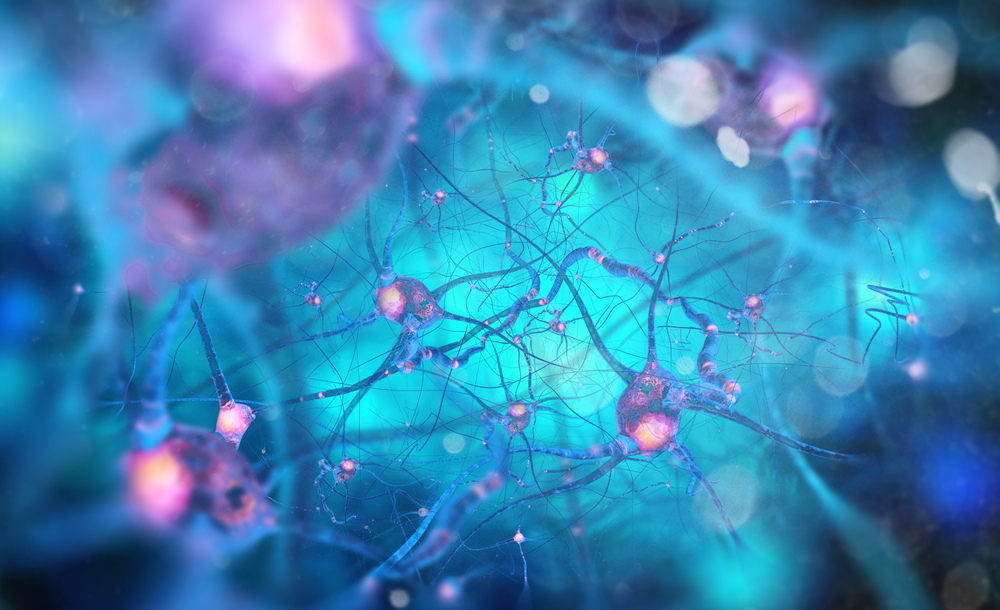

ALS is a neurological disease in which nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord are attacked in a process called neuroinflammation, which causes the loss of muscle movement control and muscle deterioration. The disease is progressive, meaning the symptoms worsen over time.

Neuroinflammation seems to play an important role in disease progression and is thus a promising therapeutic target.

CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T-cells, a type of immune cell also known as Tregs, are responsible for shutting down the immune response after successfully eliminating invading organisms from the body. Basically, these cells work as policemen to a possibly overreactive immune system.

Tregs are also able to infiltrate the brain and spinal cord and reduce neuroinflammation. However, little was known about Treg effects on animal models or humans with ALS.

In this multicenter human and animal study, researchers investigated the relationship between Tregs and the progression of ALS in humans. They also studied how the number of Tregs influenced the therapeutic outcome in a mouse model of the disease.

Clinical, functional, and immunological studies were first conducted on 33 patients with sporadic ALS, as well as 38 healthy control participants.

In a second phase, the team developed a novel approach to increase the number of Tregs in a mouse model of ALS.

Results of both studies showed that Treg levels are closely linked to ALS progression. In fact, researchers found that, in both humans and mice, the higher the levels of Tregs, the slower the disease progression.

“We wanted to understand the relationship between Tregs and ALS. We measured the levels of Tregs in patients with ALS, and we found that the disease progressed significantly more slowly in patients who had higher numbers of Tregs in their blood,” Fiona McKay, PhD, co-lead author of the study, from the Westmead Institute for Medical Research in Australia, said in a press release.

“Treg populations were expanded in the mouse model using a treatment never previously used for this disease. Not only did the disease progress more slowly, but the motor neurons were preserved,” she said. “This extends the findings of our human studies, and we are now investigating strategies to increase Tregs in patients with ALS. We hope this will ultimately lead to new therapies to treat the disease.”