SARM1 Inhibition Has Potential to Prevent Neurodegeneration in ALS, Other Diseases, Preclinical Results Suggest

Written by |

Inhibition of the SARM1 gene can prevent the degeneration of nerve cells in the central, ocular, and peripheral nervous system in mice, results from preclinical studies show.

These findings provide evidence for the use of small-molecule inhibitors of the SARM1 protein being developed by Disarm Therapeutics as potential disease-modifying therapeutics for several disorders, including multiple sclerosis (MS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), glaucoma, and peripheral neuropathies.

Preclinical data demonstrating this therapeutic potential was recently discussed at the Neuroscience 2018 conference in San Diego, in the poster “SARM1 Deletion Prevents Degeneration of Peripheral and Central Axons.”

“The data presented at Neuroscience 2018 are important milestones in Disarm’s work as we develop small-molecule inhibitors that prevent axonal degeneration in diseases such as multiple sclerosis and peripheral neuropathies,” Rajesh Devraj, PhD, founder and chief scientific officer of Disarm Therapeutics, said in a press release.

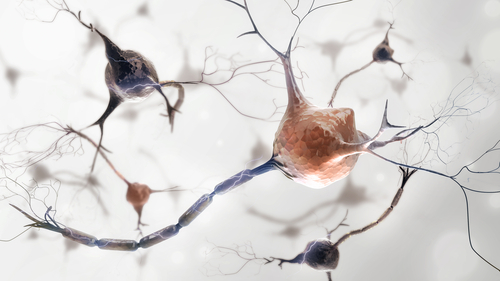

Nerve cells have a long projection of nerve fiber called an axon, which is essential to conduct electrical impulses. Damage or degeneration of this structure is the underlying feature in a broad range of traumatic, inflammatory, and neurological diseases.

Axonal degeneration often occurs in the early stages of the disease course, holding great potential for therapeutic targeting strategies.

Disarm’s scientific founders previously discovered that the SARM1 protein in nerve cells can trigger axonal degeneration.

Results from preclinical studies have revealed that genetic deletion of the SARM1 protein can protect the axon structure of nerve cells from both forced injury and damage caused by anticancer agents, such as paclitaxel and vincristine.

In addition, in the absence of SARM1, researchers noted a significant reduction of neurofilament light chain (NfL), which is a widely recognized biomarker of axonal degeneration. This finding provides further evidence that inhibition of the SARM1 protein can protect nerve cells from damage.

Using mouse models of different types of nerve cell damage, the research team demonstrated that by evaluating levels of cADPR — a compound that results from SARM1 activity — and NfL in the blood, it was possible to track central, peripheral, and ocular nerve damage mediated by SARM1.

These results provide evidence of the therapeutic potential of SARM1, and support the development of Disarm’s small-molecule SARM1 inhibitors as potential disease-modifying therapeutics.

“We now have validated biomarkers that measure SARM1 activity and axonal degeneration. These are important tools for translating our therapies rapidly into human clinical trials and, ultimately, to patients,” Devraj said.

The company has already discovered new, potent SARM1 inhibitors and is advancing them into a preclinical development program, according to its website.