Nerve Injury Progressing in Top-down Manner Evident in Bulbar ALS

Written by |

Most people with bulbar onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) showed distinct signs of motor neuron injury starting in the bulbar region of the brain that controls swallowing and speaking, before symptoms descended to regions that control the upper limbs and then the lower limbs, a small study of the disease’s spread patterns found.

Some of its patients, however, showed a different and “non-contiguous” pattern of nerve injury progression, leading the investigators to recommend follow-up assessments for these people.

The study, “The rostral to caudal gradient of clinical and electrophysiological features in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with bulbar-onset,” was published in the Journal of International Research.

Bulbar onset ALS (BO-ALS) first affects muscles involved in speaking, swallowing, and breathing, leading to slurred speech and difficulties in swallowing. Muscle weakness can progress rapidly to the arms and legs, making it more difficult to distinguish between bulbar and spinal ALS.

Electromyography, in which a small needle electrode is inserted into the muscle to deliver or detect electrical signals, used to help detect neuromuscular abnormalities.

EMG has helped scientists document how muscle abnormalities spread throughout the body in general ALS cases, but not among those with bulbar ALS.

Researchers based at the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University in China reviewed the medical records of 57 bulbar ALS patients who had undergone EMG for diagnosis, to further an understanding of the electrophysiological features and distribution of muscle abnormalities in bulbar ALS.

“The present study aimed to clarify the distributive patterns of clinical and electrophysiological features in patients with BO-ALS,” the researchers wrote.

Patients ranged in age from 35 to 83 (average age of 57), and all reported initial symptoms in the bulbar region, including speech problems in 52 patients and trouble swallowing in 37 others. The mean time interval from symptom onset to diagnosis (diagnostic latency) was 11.3 months.

A majority (84.2%) had a single-site onset, while 15.5% showed initial symptoms in more than one body area. In 37 patients, symptoms spread to neighboring body regions, starting in the bulbar region and to the upper limbs in 33 patients, and then to the lower limbs in 19 patients.

In two patients, symptoms spread to the upper and lower limbs simultaneously after bulbar onset, and upper limb weakness developed along with bulbar symptoms in another two, followed by lower limb symptoms.

In contrast, six patients progressed in a non-continuous manner, in which five patients showed leg symptoms right after bulbar-onset, and four of them went on to develop upper limb (arms) symptoms. In one of these patients, symptoms were initially in both the bulbar and lower limb regions.

Among 43 patients who with progressing symptoms, the mean time interval for their spread to a different body area was 8.2 months, ranging from 0.3 to 32 months.

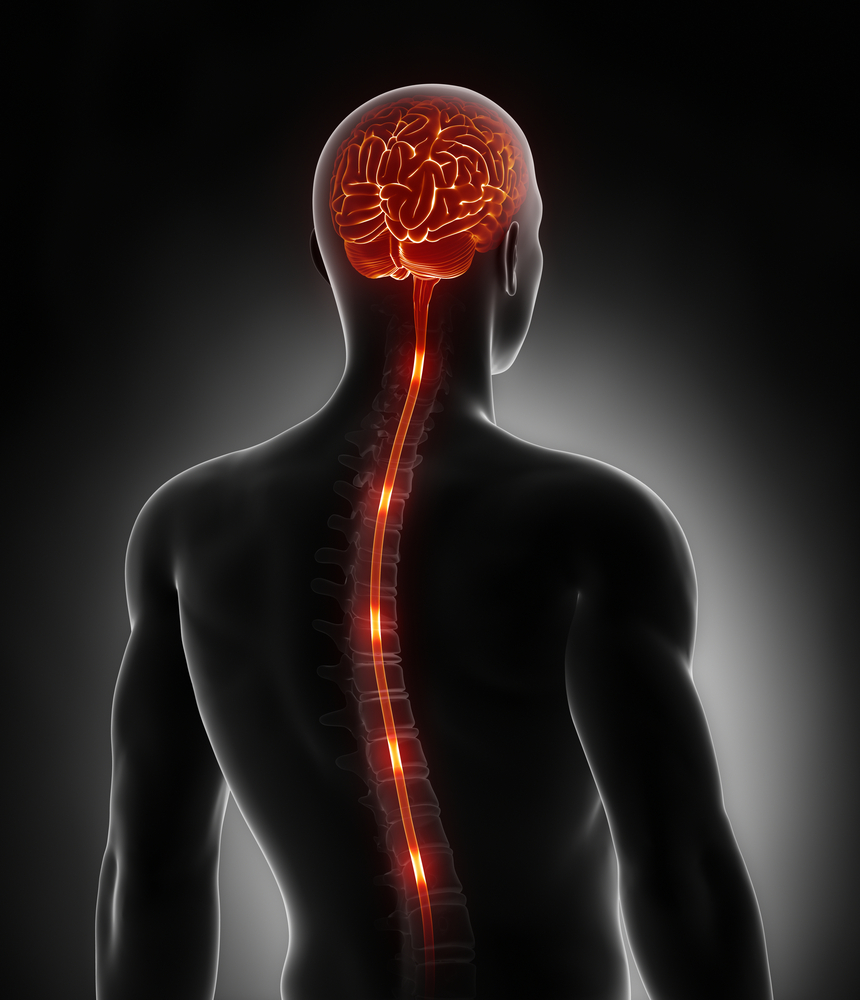

Using EMG, distribution of problems in lower motor neurons (LMNs) — which lead from the spinal cord or brain stem to muscles, causing weakness, muscle twitching, and wasting — was significantly different in muscles connected to bulbar nerves (innervated) than those connected to nerves of the lower back (controlling leg muscles).

Despite the non-continuous spreading of symptoms found in some patients, the most frequent lower motor nerve involvement was found in the bulbar region (rostral), followed by the upper limbs, then the lower limbs (caudal).

“A descending gradient of LMN dysfunction from rostral to caudal regions in BO-ALS was observed,” the investigators wrote.

In contrast, involvement of the upper motor neurons (UMN), which lead from the brain and brainstem and carry signals to lower motor neurons, was found in most patients, but there were no significant differences in body regions.

Overall, affected neurons were more frequently found in muscles connected to nerves from the bulbar and neck regions than those connected to nerves from the upper or lower spinal cord.

Of these 57 patients, 16 showed injury to neurons in the bulbar and neck area, but not those of the spinal cord. These patients had better neurological function as measured by the ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-R) score than the 41 other patients who showed nerve involvement in the bulbar, neck, and spinal cord regions.

Researchers also divided patients based on diagnostic latency: one group of 40 patients were diagnosed more than six months after symptom onset, while the other 17 had a diagnostic latency of six months or less. There were no significant differences in sex, age, age of onset, or ALSFRS-R score between them.

The time from the onset of initial symptoms in one body area to a different area was significantly shorter in those with more recent diagnosis (mean diagnostic latency of 3.66 months) than for those with a longer latency (mean of 7.25 months). According to the researchers, “this might contribute to the early definite or probable diagnosis.”

Patients with a shorter diagnostic latency also had a lower incidence of neurological changes in nerves of the lower back compared to those with longer diagnostic latency.

Despite this, nerve injury in patients with a shorter diagnostic latency was “detected as early as within 6 months after the onset, much earlier than the occurrence of clinical manifestations in lower limbs reported as 14 months,” the researchers wrote.

“These results may help understand the clinical and electrophysiological progression of BO-ALS and suggest that follow-up EMG might be necessary for at least a proportion of patients,” the team concluded.