Brain Implant Helping ‘Locked-In’ ALS Patient to Communicate, Even Outdoors

Written by |

A woman with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), who had lost nearly all capacity to communicate, is now able to successfully interact with her surroundings using a brain-computer interface implant, according to a recent article in New Scientist magazine.

The device is thought to be the first used in a patient’s daily life, without the need of daily recalibration that hampered earlier efforts with electrodes, Jessica Hamzelou reported in the article. It demonstrates the feasibility of giving “locked-in” patients their voice back.

Data on the device and its use was presented at the Society for Neuroscience 2016 Annual Meeting, running through Nov. 16 in San Diego.

The poster presentation, “Autonomous communication at home by a person suffering from Locked In Syndrome achieved with a completely implanted permanent Brain-Computer Interface system,” detailed the overall development and successful application of the system, developed by Dr. Nick Ramsey and his research team at the Brain Center of University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands.

The team shared the implant’s technical details in several other presentations at the meeting.

The woman, now 58 years old, was diagnosed with ALS in 2008, and is in an almost completely locked in state. She can only move her eyes, and relied on an eye-tracking device to spell words, but the risk of losing this ability as well is substantial.

Brain-computer interface devices have been a hot topic for a while, but as converting a brain signal to a computer command is an intriguingly complex process, researchers have struggled to make devices simple enough to use everyday at home with wireless technology.

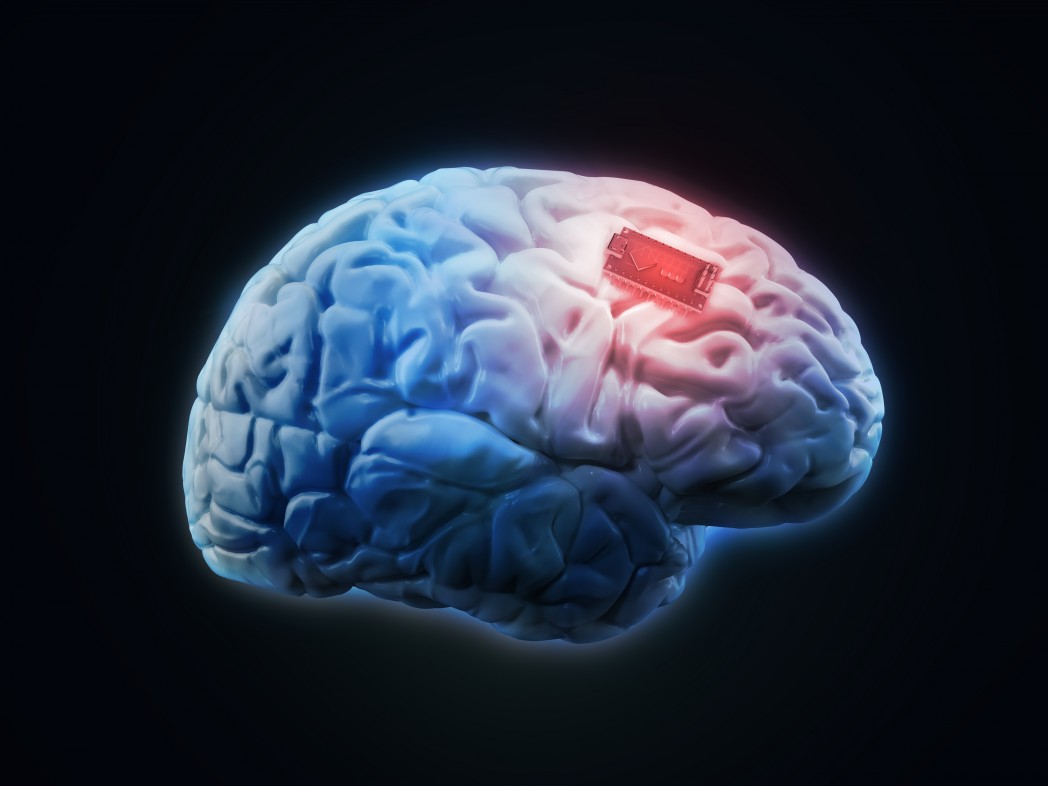

The new brain implant, consisting of several strips of electrodes placed on the brain’s surface, is inserted through holes in the skull. The electrodes were placed in a brain area that corresponded to movement of the woman’s right hand.

When the woman is thinking of moving her hand, signals are sent to a small device that translates the signal to a form that can be read by a computer. The device is inserted under the skin on the chest, and enables the patient to “click” on the screen of a tablet to spell out words.

Researchers first had to train the woman and evaluate various aspects of the system’s reliability, but after six months of using the device, she is picking up both speed and accuracy. And should she lose control over the brain area commanding her right hand, a backup system exists that relies on her counting backward.

While the device and its software can be used to click and spell words, software improvements are on the team’s wish-list. Such advances would allow prediction of words after a few letters, or be used for completely different functions, such as managing home appliances.

Researchers now hope to test the device on additional patients, and expect that mass production would make the device affordable. They noted that the surgery is a straightforward process, taking four hours to complete.

New Scientist has also published an interview with the patient about her experience of the implant.“Now I can communicate outdoors when my eye-track computer doesn’t work,” the woman, who wished to remain anonymous, told the publication. “I’m more confident and independent now outside.”