Ventilation Support May Explain Why African American ALS Patients Live Longer

Written by |

Rates of invasive assisted ventilation are 3.2 times higher in African Americans with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) compared to Caucasian patients, which may explain why African American patients live longer, according to a recent study.

The study, “Racial differences in intervention rates in individuals with ALS: A case-control study,” was published in the journal Neurology.

ALS is a progressive neurological disease that affects nerve cells that control voluntary movement, called motor neurons. When these neurons die, patients are no longer able to walk or talk and eventually become totally paralyzed. This means that patients also lose their ability to breathe on their own.

Although ALS is more prevalent in the Caucasian population, the retrospective study, conducted by a team of researchers from North Carolina’s Wake Forest Baptist Health, showed that African American patients had better survival rates.

They performed a retrospective analysis of 49 African Americans diagnosed with ALS and 137 Caucasian patients matched for age, gender, and site of disease onset.

The team observed that African American patients had longer survival than Caucasians. However, this was no longer significant if the outcome was death or tracheostomy and invasive ventilation (TIV).

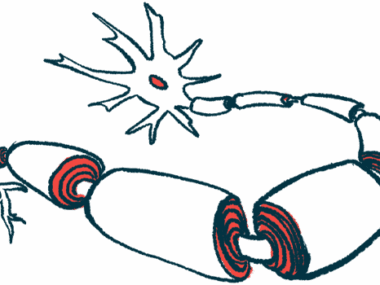

In a TIV procedure, a clinician opens a small hole at the front of a patient’s neck. A tube with a ventilator attached is inserted into the windpipe (trachea) to help the patient breathe.

In the United States, only around 2% of ALS patients undergo a TIV procedure. However, researchers observed that the African American patients were more often given a TIV — 3.2 times more — than Caucasian patients (16 percent vs 5 percent, respectively).

“Our research suggested that African Americans lived longer because they received tracheostomies at a higher rate than Caucasians,” Michael Cartwright, professor of neurology at Wake Forest Baptist and the study’s lead author, said in a press release.

Moreover, while 70 percent of the Caucasian patients underwent non-invasive ventilation (the use of a mask or similar device to help in breathing, but without the need to insert a tube into the trachea), only 55 percent of African Americans used this type of breathing support.

“Although we couldn’t pinpoint why African Americans had more tracheostomies in our study, we do know that earlier interventions, such as breathing masks, can slow down the rate of decline and help patients deal with the disease,” Cartwright said.

Overall, these findings suggest that the enhanced lifespan of African Americans with ALS compared to Caucasian patients may be due to their more frequent use of TIV.

“We think it is very important for people dealing with the disease to think about their quality of life and decide what interventions are most important to them,” Cartwright said. “As doctors we can advise and help them make these decisions beforehand rather than in emergency situations, as is often the case with tracheostomies.”