Infusing Treg Immune Cells Has Potential to Slow ALS, Small Study Suggests

Results from a Phase 1 clinical trial reveal that giving patients infusions of a specialized immune cell may be a viable option to safely slow the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

That finding was reported in the study “Expanded autologous regulatory T-lymphocyte infusions in ALS,” published recently in the journal Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation.

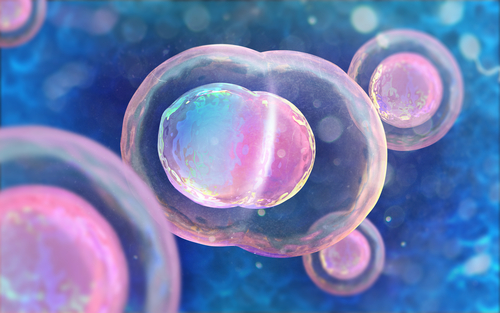

Increased neuroinflammation is an important contributor to the progression of ALS, which makes it an attractive therapeutic target. Recent studies have suggested that a subgroup of immune cells called regulatory T cells, or Tregs, could take part in this strategy.

Tregs have the ability to regulate the activity of other immune cells, acting as a stop sign when the system is overreactive. Because these cells can infiltrate the brain and spinal cord, they hold the potential to reduce the inflammation characteristic of ALS.

Researchers at Houston Methodist Neurological Institute found many ALS patients not only have reduced numbers of Tregs, but also that these cells have impaired activity. In light of these findings, the team believed that by improving the numbers and function of Tregs in patients it would be possible to achieve meaningful clinical benefits.

To explore this hypothesis, the researchers conducted a very small Phase 1 trial (NCT03241784) to determine the safety and tolerability of Tregs infusion in patients at different stages of ALS.

The study enrolled three patients with arm, bulbar, and leg-onset ALS who underwent leukapheresis. This is a process by which each patient’s white cells are collected and isolated, while the remaining components of the blood are infused back into the body. Next, the Tregs were isolated from other white cells and expanded in the laboratory to increase their numbers to a sufficient amount necessary for the treatment protocol.

Each patient received a total of eight infusions of Tregs with administration of IL-2 injections to support the cell’s survival and proliferation in the body. The first four infusions were given every two weeks at early stages of the disease, followed by four additional infusions four weeks apart at a later stage.

“A person has approximately 150 million Tregs circulating in their blood at any given time,” Jason Thonhoff, MD, PhD, said in a press release. Thonhoff is a Houston Methodist neurologist and lead author of the study. “Each dose of Tregs given to the patients in this study resulted in about a 30 to 40 percent increase over normal levels.”

In general, the treatment had an acceptable safety profile and was well-tolerated by patients.

Blood analysis revealed that the numbers of Tregs increased in all three patients after the first round of treatment. During the period in which the patients stopped receiving the infusions the percentage of Tregs declined, but increased again when the second round of treatment began. Interestingly, the suppressive function of the cells also showed a similar pattern of enhanced activation after each treatment cycle.

Assessment of disability revealed that during the treatment period the disease progressed at a slower rate in all patients. This suggests that increased Treg suppressive function is associated to slower functional decline, the researchers wrote.

“As we believed, our results showed it was safe to increase their Treg levels,” said Stanley H. Appel, MD, chair of the department of neurology at Houston Methodist and senior author of the study. “What surprised us was that the progression of their ALS dramatically slowed while they received infusions of properly functioning Tregs.”

Supported by these positive results, the team is planning to launch a Phase 2 study to further evaluate the safety and effectiveness of Tregs transplants in slowing ALS progression.

“My hope is that this research changes ALS from a death sentence to a life sentence. It won’t cure a patient’s disease, but we can make a difference,” Appel said.