Environmental pollutants in blood linked to ALS risk, survival

Greater exposure to a mix of chemicals tied to higher odds of developing ALS

A person’s degree of exposure to multiple environmental pollutants — reflected by their presence in the blood — may be used to predict amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) risk and survival, according to new research.

Greater exposure to these chemicals was associated with increased odds of an individual developing ALS, as well as a higher mortality risk among ALS patients in Michigan.

“Our results emphasize the importance of understanding the breadth of environmental pollution and its effects on ALS and other diseases,” Eva Feldman, MD, PhD, the study’s senior author and a professor at the University of Michigan (UM) and its medical school, said in a university news story.

“When we can assess environmental pollutants using available blood samples, that moves us toward a future where we can assess disease risk and shape prevention strategies,” added Feldman, also the director of the NeuroNetwork for Emerging Therapies at Michigan Medicine.

The study, “Environmental risk scores of persistent organic pollutants associate with higher ALS risk and shorter survival in a new Michigan case/control cohort,” was published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Levels of 24 environmental pollutants found to impact survival in ALS

ALS is believed to arise from a combination of genetic and environmental risk factors, such as exposure to pesticides, heavy metals, or electromagnetic fields.

The scientists previously found that concentrations of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) were higher in the blood of ALS patients compared with the general population. POPs are hazardous chemicals that are widely distributed and live in the environment for a very long time. The most common ones are pesticides or insecticides used for agriculture.

In a follow-up study, the team found that high exposure to these pollutants was associated with lower survival among ALS patients.

Now, the scientists aimed to validate their findings in a new group of patients, using the information to develop an environmental risk score (ERS) based on these exposures that could predict ALS risk and survival.

The team examined blood levels of 36 different POPs among 164 ALS patients seen at UM’s Pranger ALS clinic, as well as 105 people from the general Michigan population, who served as controls.

Characteristics between the two groups were similar, except that the ALS patients were older, and had lower educational attainment than the controls. The ALS group also had a higher proportion of men.

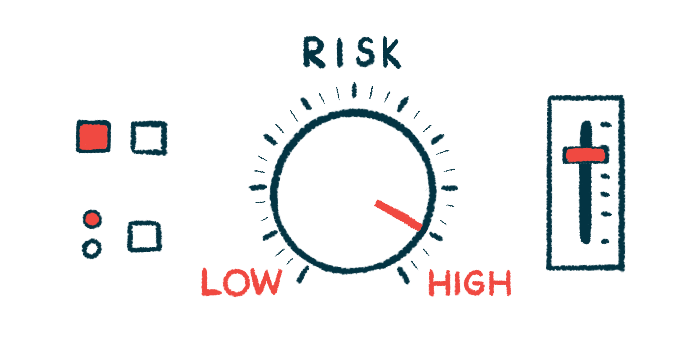

Several individual pollutants were significantly associated with ALS. Still, the researchers found that the highest risk of the neurodegenerative disease didn’t arise from just one of them, but rather a mixture of several. That mixture was used to generate a risk score for predicting the likelihood of ALS.

The results showed that scores in the 75th percentile — the threshold for the highest 25% of exposure — were significantly linked to 2.58 times greater odds of developing ALS compared with patients in the 25th percentile, or the threshold for the lowest 25% of exposure.

“For the first time, we have a means collecting a tube of blood and looking at a person’s risk for ALS based on being exposed to scores of toxins in the environment,” said Stephen Goutman, MD, director of the Pranger Clinic, associate director of the ALS Center of Excellence at UM, and the study’s first author.

Overall, 24 of 36 POPs were found to have a negative effect on ALS survival. However, survival time was best predicted by taking into account all 36 of the toxins.

Survival ERSs based on exposure to all toxins indicated that greater exposure was associated with shorter survival, as expected.

Particularly, the 25% of patients with the highest exposure had a 2.31 times greater mortality risk than the 25% of those with the lowest exposure — corresponding to a survival benefit of 0.88 years for that group.

For the first time, we have a means collecting a tube of blood and looking at a person’s risk for ALS based on being exposed to scores of toxins in the environment.

Of the individual POPs, organochlorine pesticides, known as OCPs, were most strongly associated with ALS risk and survival, which the researchers noted is in line with multiple previous analyses. OCPs are a class of pesticides that have been used since the mid-1900’s for agriculture and mosquito control.

While many previous studies have estimated environmental exposures using geographical location or occupational history, the researchers believe that directly measuring their levels in the blood may be a more accurate and quantifiable way of assessing exposure.

Still, “replication in other non-Michigan cohorts is beneficial to determine the national and global distribution of this risk,” the researchers wrote.

The findings also highlight the possible use of ERSs for understanding the impact of environmental pollutants on human disease.

“Environmental risk scores have been robustly associated with other diseases, including cancers, especially when coupled with genetic risk. This is a burgeoning application that should be further studied as we deal with the consequences of pollutants being detected throughout the globe,” Feldman said.