Top Scientist and Tattooed Patient Jointly Spur ALS Research in Sweden

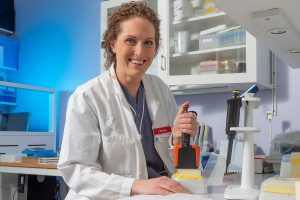

Karolinska Institute researcher Caroline Ingre has spearheaded a national ALS patient registry in Sweden, a Stockholm-area tissue biobank, and the country's first ALS clinical trials. (Photo courtesy of the Karolinska Institute)

Sweden, a nation of 10 million people, is becoming a major force in European ALS research through the recent opening of a clinical trials facility at Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute and Karolinska University Hospital.

Besides recruiting dozens of patients for trials there and in other countries, Swedish researchers have also started a national patient registry and a biobank that collects the tissue, hair, blood, and spinal fluid of patients in the Stockholm area every six months. Studies based on this material may explain some of the mysteries of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), says Caroline Ingre, MD, PhD, who leads Karolinska’s ALS research program.

The biobank material is already being used to develop multiple-molecule biomarkers that can diagnose and predict progression of the disease, Ingre told ALS News Today by phone.

Patients largely credit Sweden’s surge in ALS research activity to Ingre, who has both a medical degree and a PhD in ALS genetics. But Ingre herself says much of that progress is thanks to Mia Mollberg, an outgoing, energetic former waitress with the disease.

Mollberg’s volunteer work has made her a beloved figure in the ALS community. She’s also known for her two dozen tattoos, one of which depicts her as a warrior fighting ALS. She received her first tattoo in 2017, three years after her diagnosis.

One of Mollberg’s priorities is getting to know each of the country’s 1,000 patients, and encouraging them to participate in trials. With this goal in mind, she meets twice a year in Stockholm with newly diagnosed patients “to give them an idea of what it is like to live with ALS.” She also co-founded a Facebook page to help patients stay in touch and keep up with ALS developments.

Karolinska center off to quick start

A stroke of fortune led to the opening of Karolinska’s clinical trials facility in 2018, Ingre said.

One day a patient asked her: “If I did some fundraising, what would you do with the money?” Ingre replied: Start clinical trials in Sweden.

The Karolinska trials center got off to a quick start, participating in a Harvard-led study in 2018 and 2019, and a second study in 2019. It’s planning to take part in several more in 2020.

Mollberg’s bond with the rest of the ALS community meant “a lot of patients asked if they could participate in the studies,” Ingre said, adding that Swedish enrollment was so impressive that several pharmaceutical countries have asked Karolinska to join their trials. “Mia has become our most important recruiting tool when we are doing clinical trials.”

Mollberg has also forged ties with ALS patients in the rest of Scandinavia — Norway, Denmark and Finland — and represents Sweden at the European Network to Cure ALS, or ENCALS. And she is Sweden’s patient advisor to the 16-country TRICALS initiative, Europe’s largest ALS research program.

In addition, she is raising funds for the 15-year-old Ulla-Carin Lindquist Foundation for ALS Research, named for a respected TV news anchor who died of the disease.

Ingre decided to specialize in ALS back in 2006, during her neurology internship at Karolinska University Hospital. She was stunned that her first patient “looked healthy, had been healthy, didn’t have any other diseases [and] wasn’t taking any medication” but had received a diagnosis of ALS.

“It was hard to believe that you can be a runner, you don’t drink, you don’t smoke — ALS patients are usually very healthy and sporty — and then you get this debilitating disease that takes over your body,” she said.

Ingre led efforts to expand Karolinska’s ALS clinic in 2014. She also spearheaded the founding of the national patient registry and the Stockholm biobank about the same time. The Washington-based International Alliance of ALS/MND Associations has recognized her expertise by asking her to sit on its scientific advisory council.

Biomarkers may help predict disease variations

Three-fourths of Sweden’s ALS patients are in the national registry, which aims to ensure quality care across regions and help researchers track the disease’s variations, progression, treatment outcomes, and other parameters. Information comes from patient questionnaires as well as an Internet-based app that patients use to keep doctors abreast of their condition, Ingre said.

The registry data helps researchers determine the average time it takes for patients to be diagnosed with ALS and start treatment, as well as their quality of life, she said.

More than 90% of the 250 ALS patients in the Stockholm area and a number of their families contribute samples to the biobank.

“We are also doing different kinds of imaging with the patients, which helps explain ALS in a different way,” said Ingre, whose team uses biobank material for its own research and for collaborations with scientists elsewhere in Sweden and abroad.

A key focus of the biobank-based research is a search for multiple-molecule biomarkers to identify and predict the progression of ALS. The thinking behind this approach is that it will be difficult to find one or two single-molecule biomarkers that work with the disease’s many variations.

Early in her career, Ingre said, she believed ALS “was more uniform.” But over the years, she came to realize that “I almost never see patients with the same form of ALS” — as if it is several diseases instead of one, she said.

“Patients ask us all the time how their disease will progress,” Ingre said. “Because of its many variations, we simply can’t predict that accurately.”

A combination of multiple-molecule biomarkers and imaging may be able to predict how some variations of the disease will progress, she said. If that proves true, the next step would be developing biomarker packages that, collectively, could generate forecasts for a broad swath of ALS — with the ultimate objective “to treat different smaller groups within the overall cohort with different medications.”